RICHARD WAGNER

EXPLORE

An introduction to Wagner's Der Ring Des Nibelungen by Deryck Cooke

1. Of all great musical compositions Der Ring des Nibelungen is by far the largest: a consecutive performance of its four separate parts would last for some fifteen hours. To confer unity on this vast scheme Wagner built his score out of a number of recurrent themes, each one associated with some element in the drama and developed in con-junction with that element throughout the work.

In consequence, a comprehensive analysis of The Ring would be an enormous task. It would involve clarifying the psychological implications of all the motives, and tracing their changing significance throughout the whole of their long and complex development. Nevertheless, understanding and enjoyment of the work can be greatly helped by simply establishing the identity of all the really important motives, and indicating what immediate dramatic symbols they stand for which is all that this introduction is intended to do.

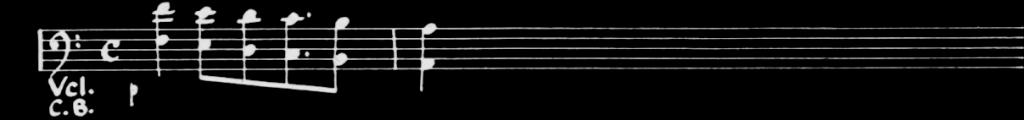

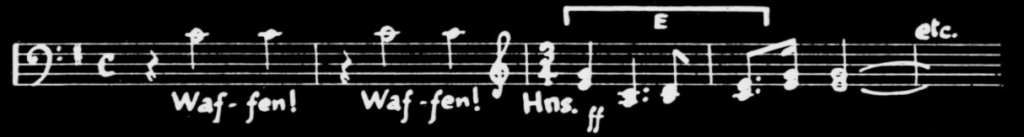

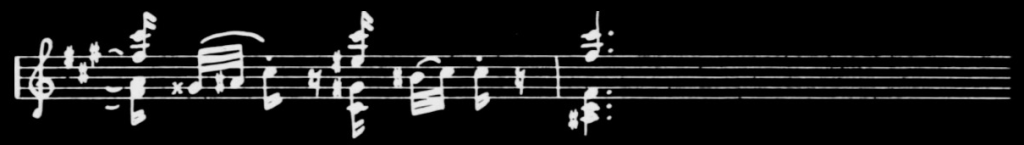

The motives are associated with four different types of dramatic symbol: characters, objects, events, and emotions. An example of a motive representing a character is the stern fanfare which introduces Hunding in Act One of Die Walküre.

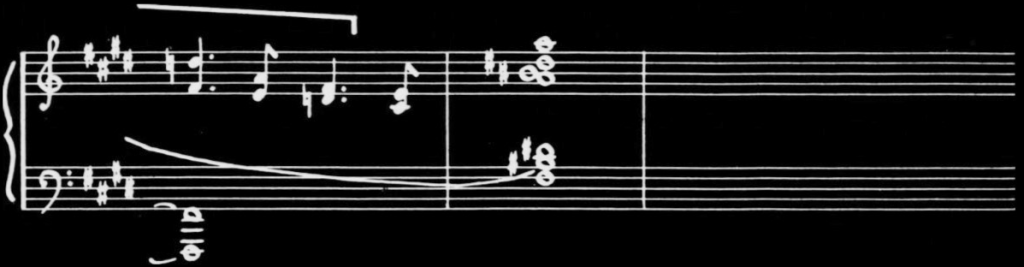

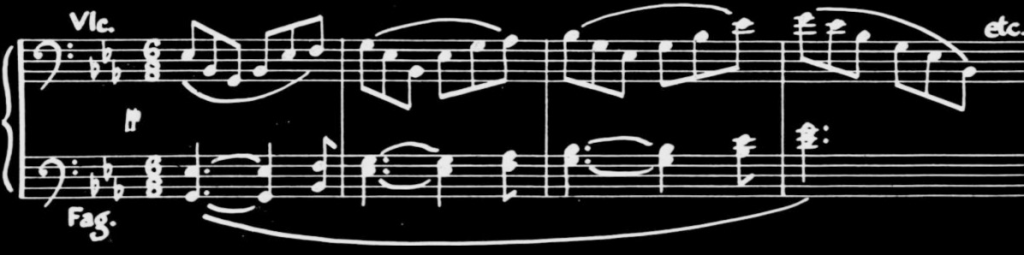

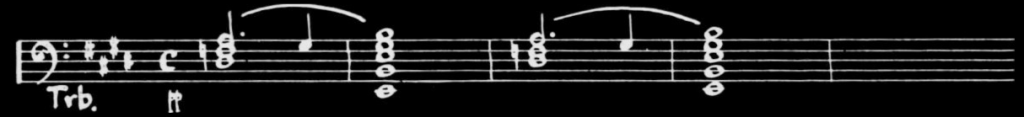

EX. 1: HUNDING

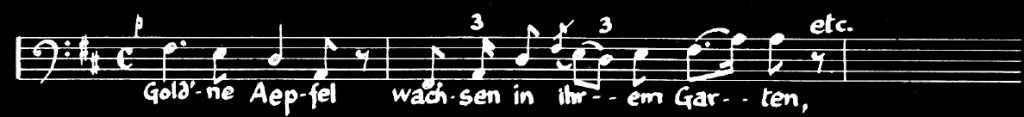

An example of a motive representing an object is the genial theme associated with Freia’s Golden Apples. This is introduced in Scene Two of Das Rhinegold; it is sung by Fafner as he explains the value of the apples to Fasolt.

EX. 2: GOLDEN APPLES

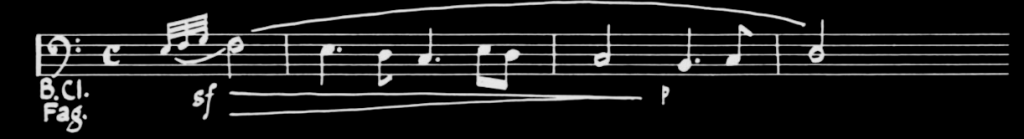

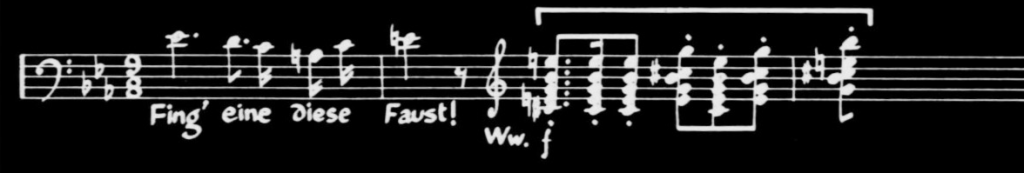

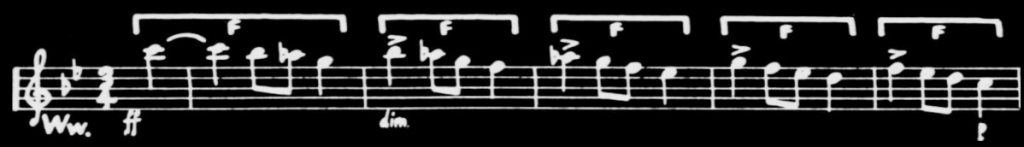

An example of a motive representing an event is the brief, agitated figure on the woodwind which follows Alberich’s Threat of violence against the Rhinemaidens in Scene One of Rhinegold.

EX. 3: ALBERICH’S THREAT

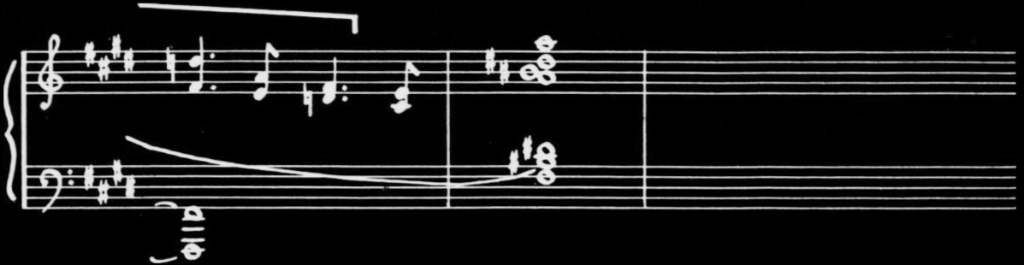

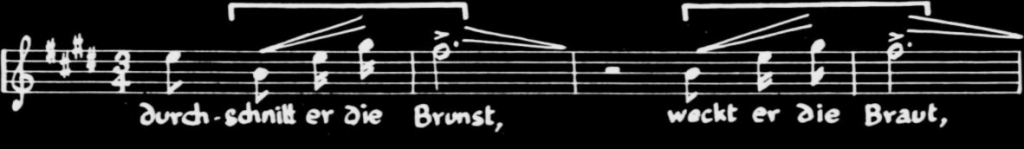

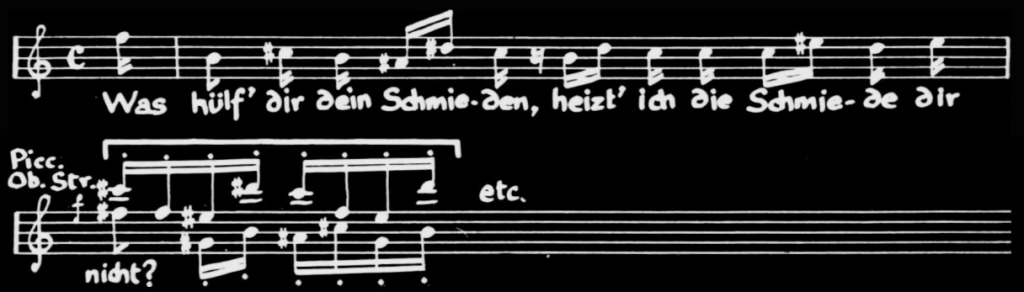

An example of a motive representing an emotion is the furious repeated figure on the orchestra which portrays Siegfried’s anger during Act One of Siegfried.

EX. 4: SIEGFRIED’S ANGER

These examples are only four of the almost innumerable motives in The Ring. But at the heart of this diversity there is a simple unity: practically all the motives arise from a few basic motives. Each of these basic motives represents one of the central symbols of the drama; and it generates a number of other motives, by a process of transformation, to represent various aspects of the central symbol concerned. And so we can thread our way through the jungle of motives in The Ring by grouping them into their different families. We can start from each basic motive in turn, and trace the family of motives it generates throughout The Ring, before continuing with the next basic motive.

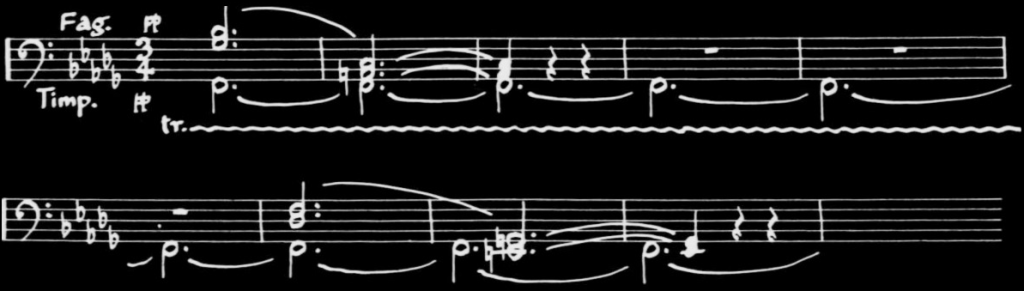

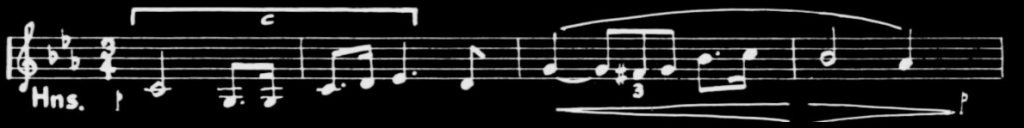

2. The fundamental symbol in The Ring is the world of nature, from which everything arises and to which everything returns. And Wagner’s basic motive for this ultimate source of existence is that fundamental element in music – the major chord. This chord, spread out melodically as a rising major arpeggio by the horns, forms the mysterious Nature Motive which opens the whole work.

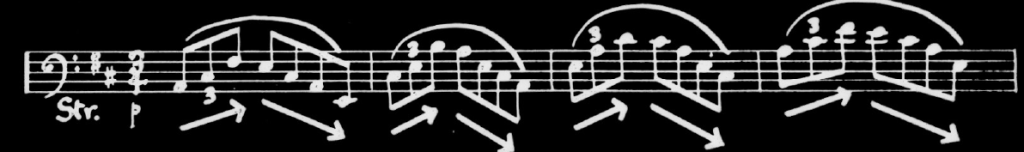

EX. 5: ORIGINAL NATURE MOTIVE

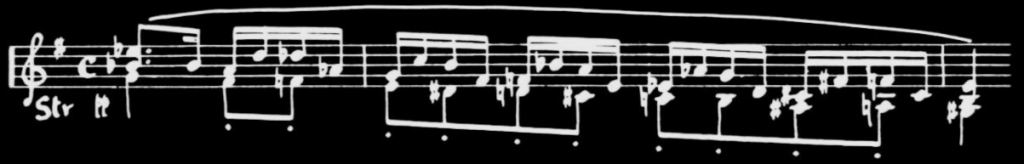

This is the original form of the Nature Motive. It soon undergoes a simple melodic transformation into a peacefully undulating string theme; and the result is what may be called the definitive form of the Nature Motive, since this is the form in which it will recur throughout the whole work.

EX. 6: NATURE MOTIVE (DEFINITIVE)

The next transformation is that this definitive form of the Nature Motive simply begins to move at twice the speed, and in so doing it becomes a new motive — the surging motive of the River Rhine.

EX. 7: THE RHINE

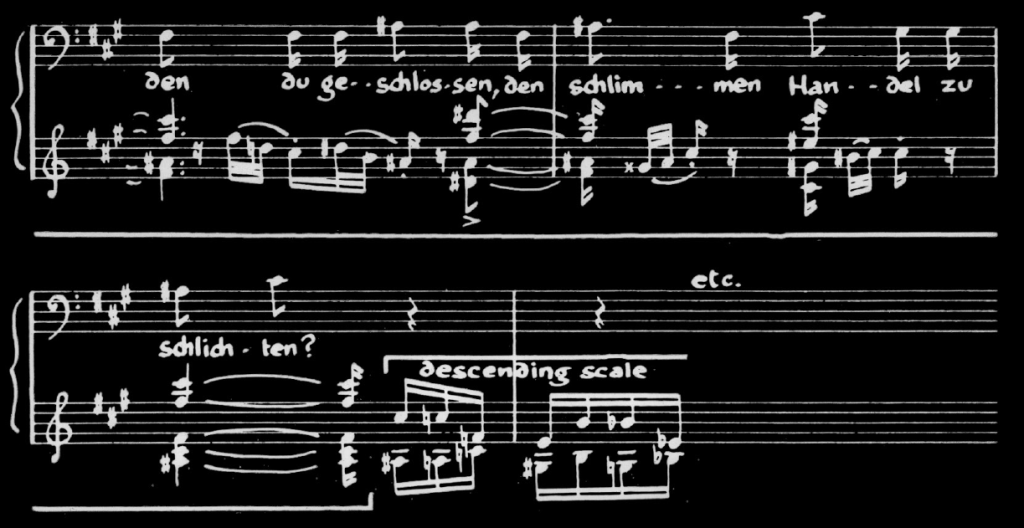

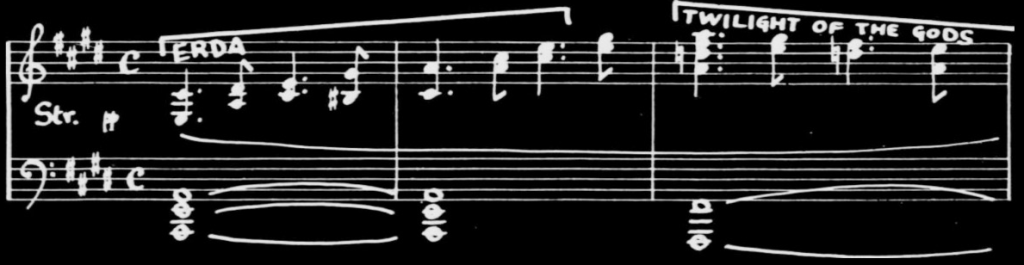

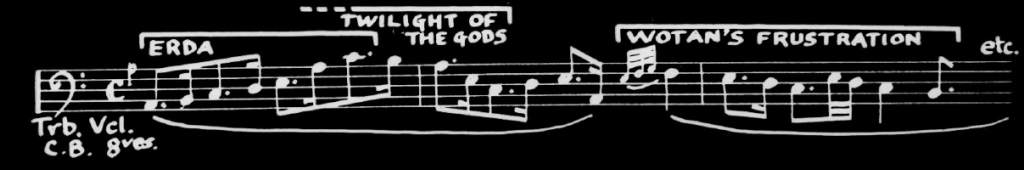

Tracing further the family of motives generated by the basic Nature Motive we must pass on now to Scene Four of Rhinegold for the next transformation. Here the Nature Motive, by turning from major to minor, and a flowing 6/8 to slow 4/4 time, becomes the dark motive of Erda – the earth-goddess.

EX. 8: ERDA

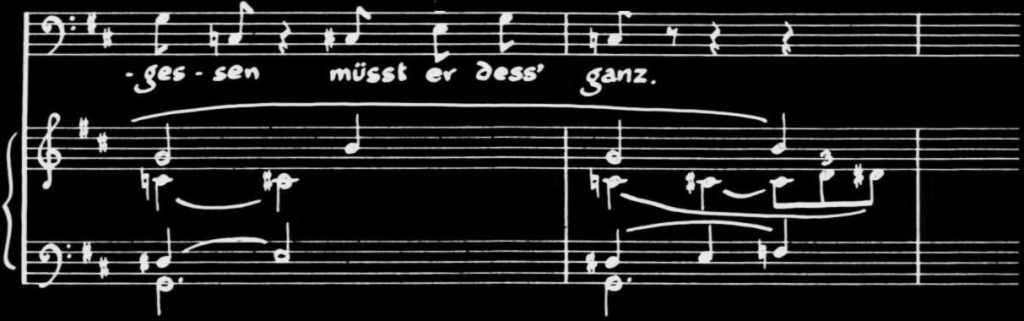

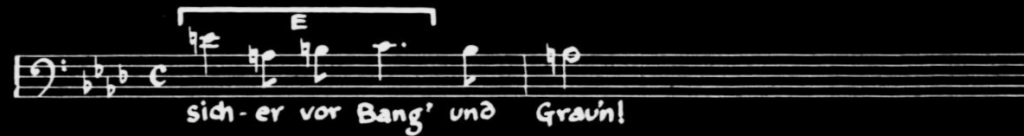

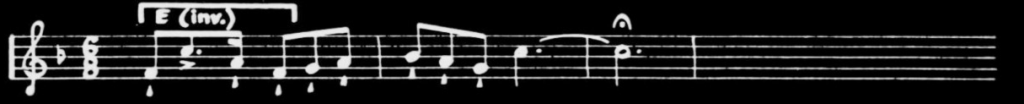

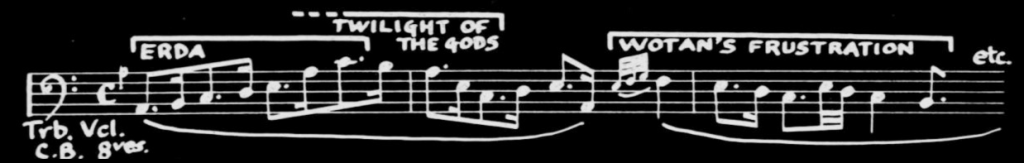

So far the transformations of the Nature Motive have been simple ones, but the next is more radical; the motive turns upside-down, implying its own opposite. When Erda begins to warn Wotan of the end in store for the gods, the orchestra accompanies her with her own motive – itself a simple transformation of the Nature Motive as we have heard; but as she comes to the .point the orchestra changes her rising motive into a falling one. The motive of life and growth becomes the motive of decay and death. Here is the whole passage: the orchestra has two statements of Erda’s rising motive followed by its inversion, the falling motive of The Twilight of the Gods.

EX. 9: ERDA/THE TWILIGHT OF THE GODS

The strings accompany Erda’s voice very softly here, only hinting at the gods’ mortality. We can hear what happens more clearly if we have the accompaniment played by the orchestra alone: first the rising Erda Motive and then immediately its inversion – the falling motive of The Twilight of the Gods.

EX. 10: ERDA/THE TWILIGHT OF THE GODS

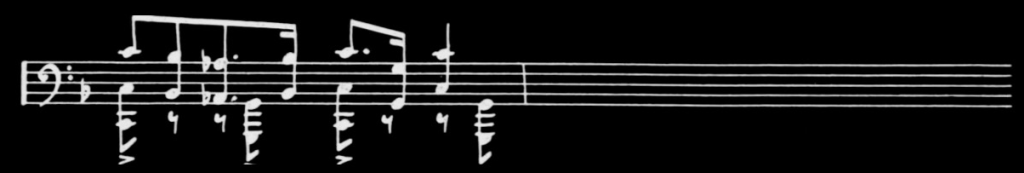

This mysterious falling, fading motive, like so many of the others, recurs at many points in The Ring. Naturally, it permeates the final part of the work – The Twilight of the Gods, Götterdämmerung – and inevitably it introduces the final scene, when Brünnhilde steps forward to perform the decisive actions that bring about the end of the gods.

EX. 11: THE TWILIGHT OF THE GODS IN ‘GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG’

3. Returning now to the Nature Motive and its further transformations: after Erda and her warning in Rhinegold, we have to wait until Act One of Siegfried for the next transformation, another simple one. This occurs when Wotan speaks to Mime of the all-powerful spear that he cut from the World’s great Ash-Tree-the Tree of Life, guarded by Erda’s daughters, the Norns. The orchestra accompanies his words with anew rhythmic variant of the Nature Motive, in the minor and in 3/4 time. Here first, as a reminder, is the Nature Motive again.

THE NATURE MOTIVE (DEFINITIVE) - EX. 6

And here is the swaying motive of the World Ash-Tree as it is introduced to accompany Wotan in Act One of Siegfried. Listen to the orchestra.

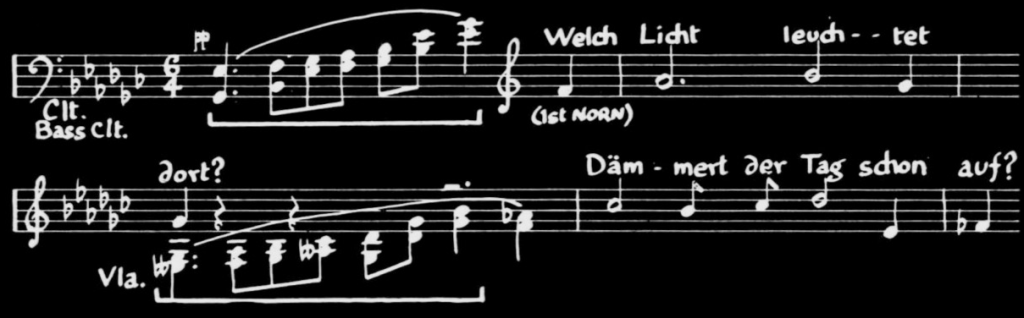

This World-Ash Motive, which has a close kinship with Erda’s Motive, recurs in The Twilight of the Gods in conjunction with Wotan’s cutting down of the tree of life to provide fuel to burn Valhalla. It permeates the scene of the Norns- Erda’s daughters - who are bewildered by this fatal act of Wotan’s.

EX. 13: THE WORLD ASH-TREE IN GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG

After the introduction of this World-Ash Motive in Act One of Siegfried, the next transformation of the Nature Motive occurs in the Second Act where Siegfried is in the forest. Wagner takes a very slow, dark, minor version of it, akin to Erda’s Motive, and superimposes on this a slowly oscillating string figuration. The result is what may be called the embryonic version of the motive of the Forest Murmurs.

EX. 14: FOREST MURMURS (EMBRYONIC)

This embryonic version of the Forest Murmurs Motive soon begins developing the oscillating figure freely, without regard to the original Nature Motive basis.

EX. 15: FOREST MURMURS (INTERMEDIATE)

Out of this development, by a process of increasing the speed of the oscillation in 9/8 time Wagner eventually evolves the definitive, shimmering major form of the Forest Murmurs Motive – the one that is to be used entirely from here onwards.

EX. 16: FOREST MURMURS (DEFINITIVE)

4. A number of further motives in the Nature family are evolved, not from the definitive form of the Nature Motive with which we have been concerned so far, but from its original form — the rising major arpeggio on the horns which opens The Ring, and with which we started. These further motives are free transformations of the original Nature Motive in that they themselves are forms of the rising major arpeggio. First, a reminder of the Original Nature Motive.

ORIGINAL NATURE MOTIVE-EX. 5

The first free transformation of this Original Nature Motive is the important motive of The Gold, which is introduced by the horns in Scene One of Rhinegold.

EX. 17: THE GOLD

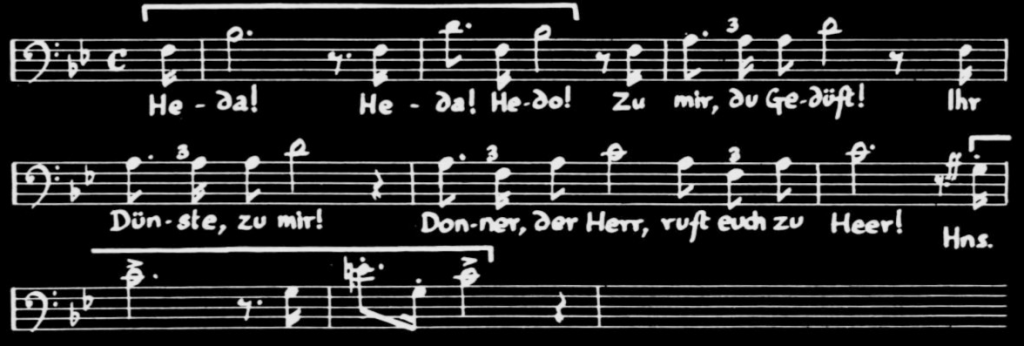

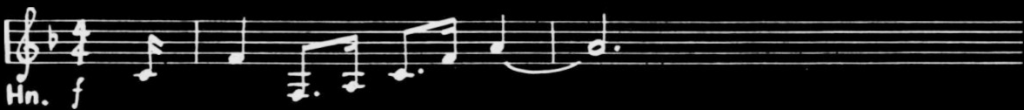

The next free transformation of the Original Nature Motive is the bold motive of Donner. He himself sings this as he calls up the storm in Scene Four of Rhinegold, and he is echoed by the horns.

EX. 18: DONNER

A third transformation of the Original Nature Motive is the rising and falling arpeggio of the theme representing The Rainbow Bridge, again in Scene Four of Rhinegold, though this is hardly a motive in the strict sense, since it never appears again.

EX. 19: THE RAINBOW BRIDGE

A further transformation of the Original Nature Motive is the heroic trumpet motive of The Sword which is also introduced in Scene Four of Rhinegold. This major arpeggio is almost identical in shape with the arpeggio of the Original Nature Motive, as we can em in the same key. Here is the Original Nature Motive as it recurs for the only time — near the beginning of Act Three of The Twilight of the Gods.

EX 20: THE ORIGINAL NATURE MOTIVE IN ‘GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG’

And here is the motive of The Sword as it recurs in Act Three of Siegfried when Siegfried uses the sword to cut away the steel breast-plate from the sleeping Brünnhilde.

EX 21: THE SWORD

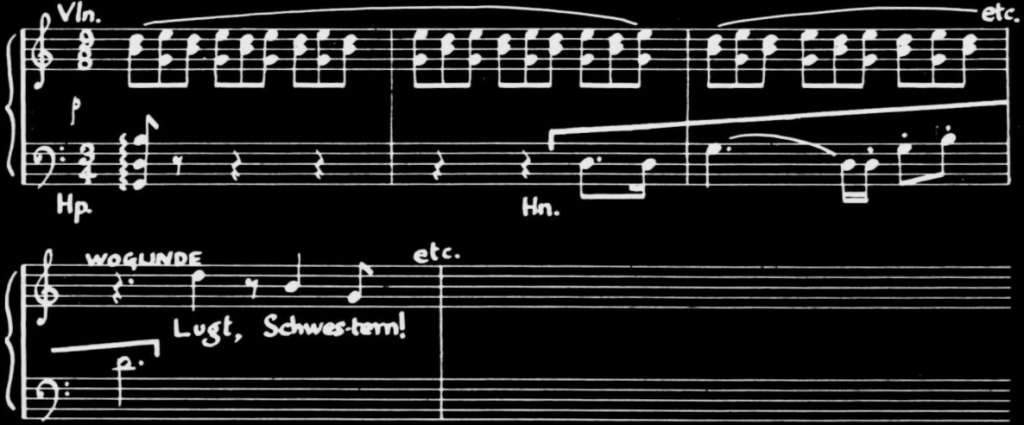

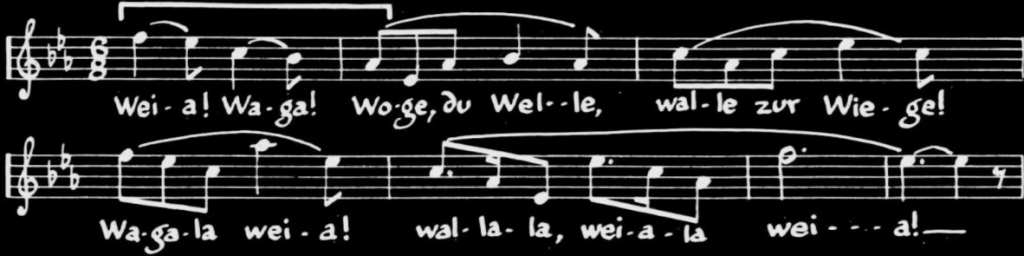

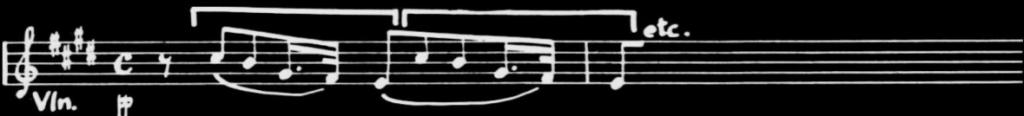

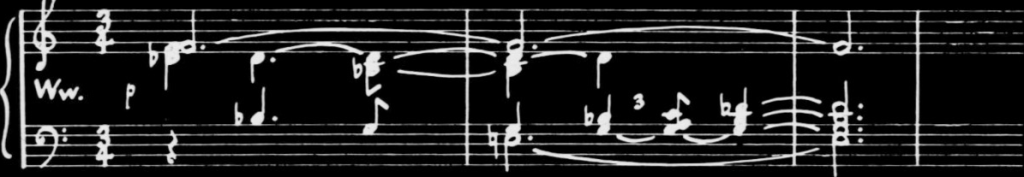

5. This completes the family of motives evolved from the Nature Motive-either from its definitive, flowing form, or from its original arpeggio form. A second, much smaller family is closely associated with this – the pentatonic family of the voices of nature. The first vocal utterance in The Ring is a voice of nature-that of the first Rhinemaiden-Woglinde; and her falling and rising pentatonic theme is the motive which is to be associated with The Rhinemaidens.

EX. 22: THE RHINEMAIDENS

This Rhinemaidens’ Motive is slightly transformed and speeded up to produce the motive of The Woodbird in Act Two of Siegfried. The Woodbird is evidently first cousin to the Rhinemaidens.

EX. 23: THE WOODBIRD

The Woodbird unlike the Rhinemaidens, is not represented by a single motive but by several other figures as well, each having the character of a bird-call. The most important of these is a phrase which is particularly associated with the Woodbird’s message to Siegfried about the sleeping Brünnhilde.

EX. 24: THE WOODBIRD (SEGMENT)

One other motive belongs to this small family-that of the Sleeping Brünnhilde in Act Three of Walküre. Brünnhilde, in her magic sleep, may not be a voice of nature but she is a latent, inspiring force of nature; and this motive of the Sleeping Brünnhilde is a rhythmic variant of the opening five notes of the motives of the Rhinemaidens and the Woodbird... Here is a reminder of the beginning of the Rhinemaidens’ Motive.

THE RHINEMAIDENS (SEGMENT) - EX. 22

And here is the rhythmic variant of the first five notes of that motive which is the motive of the Sleeping Brünnhilde.

EX. 25: THE SLEEPING BRÜNNHILDE

6. So much for nature. Standing out against this background of nature are the human actions that constitute the drama: and the intentions behind the various types of action are represented on the stage by several central symbols – Alberich’s ring, Wotan’s spear, Siegfried’s sword, and so on.

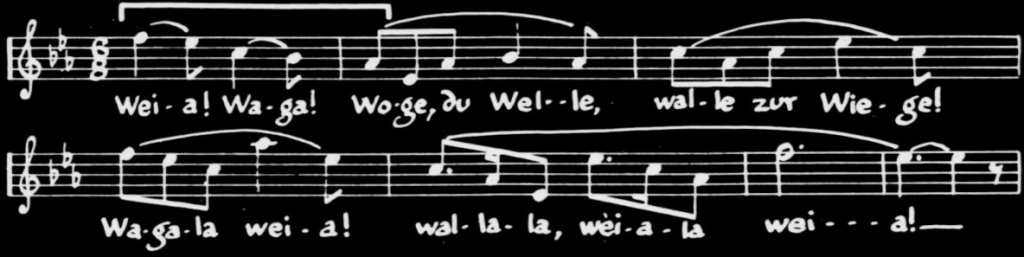

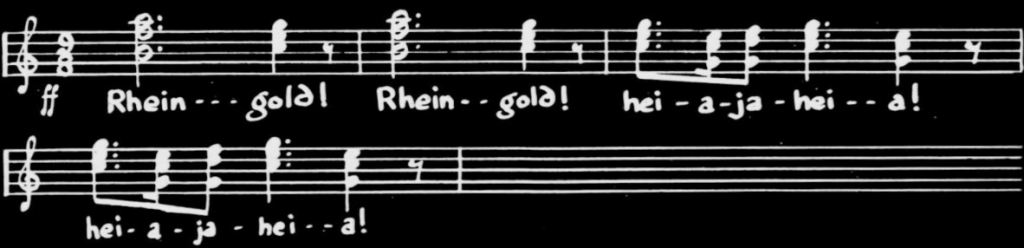

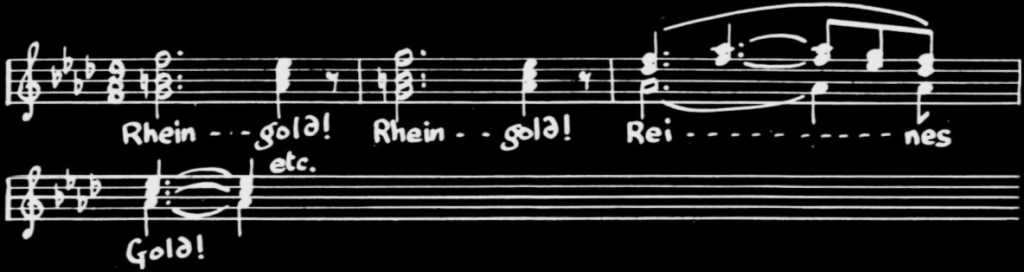

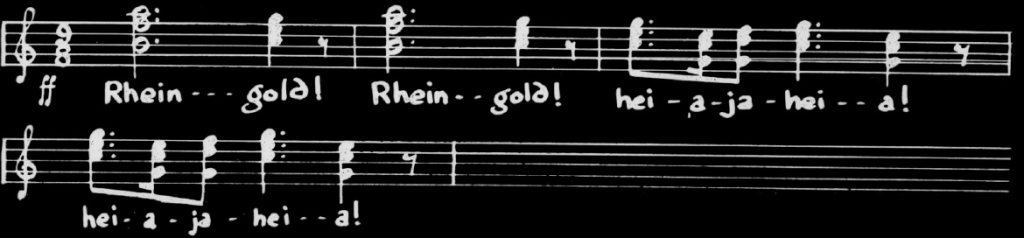

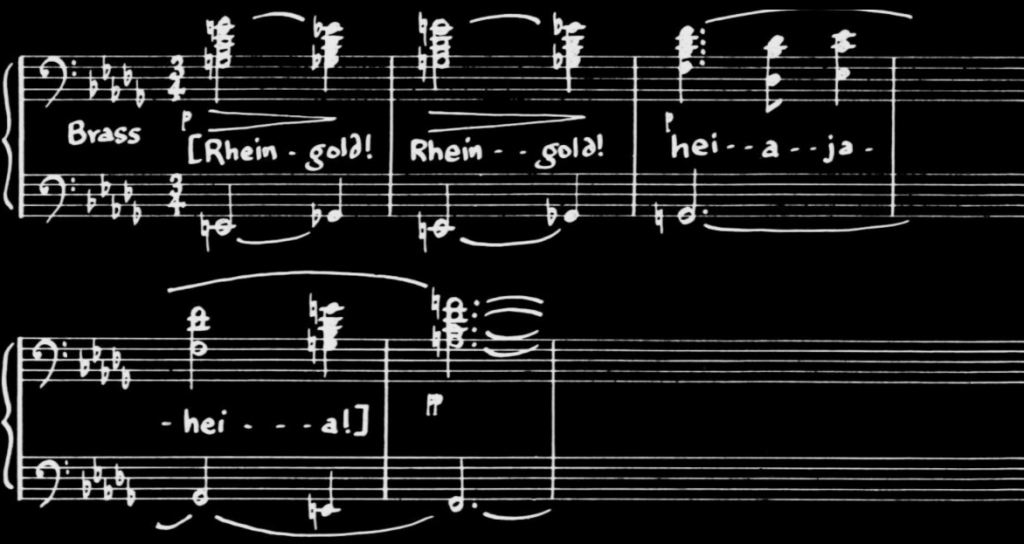

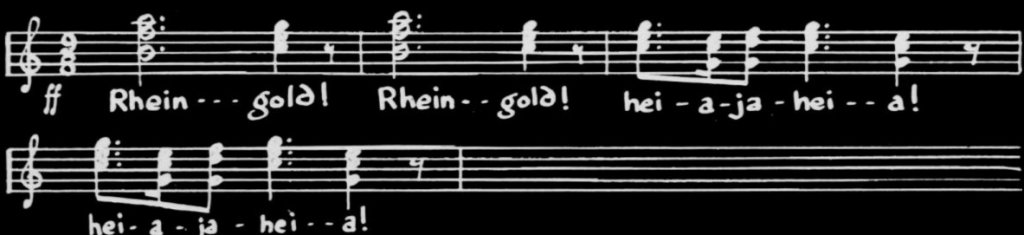

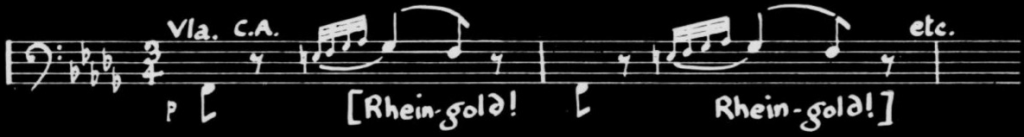

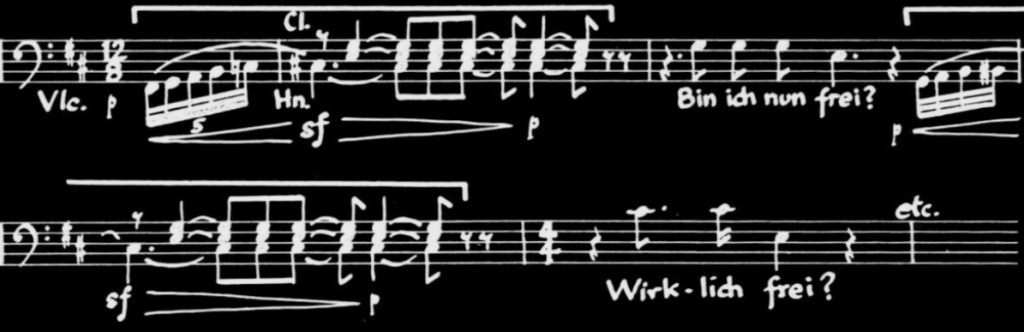

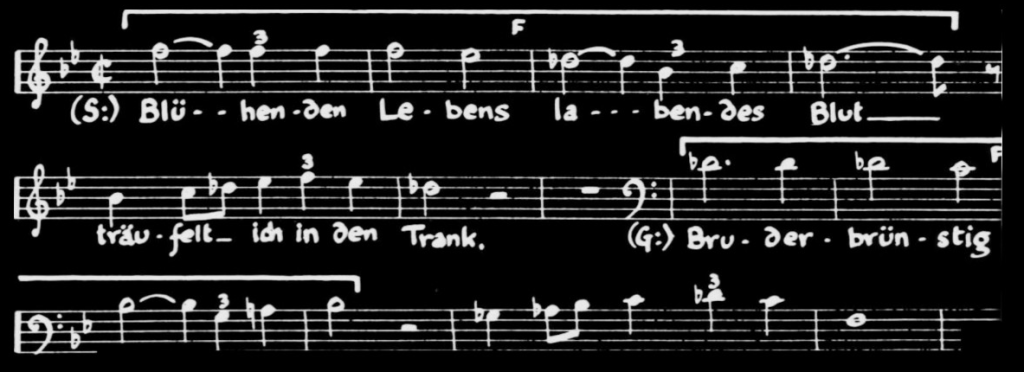

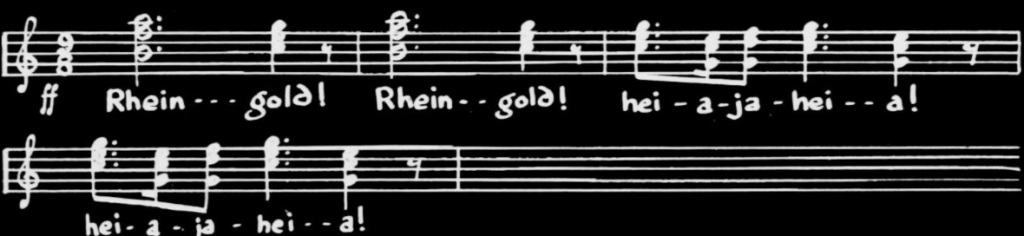

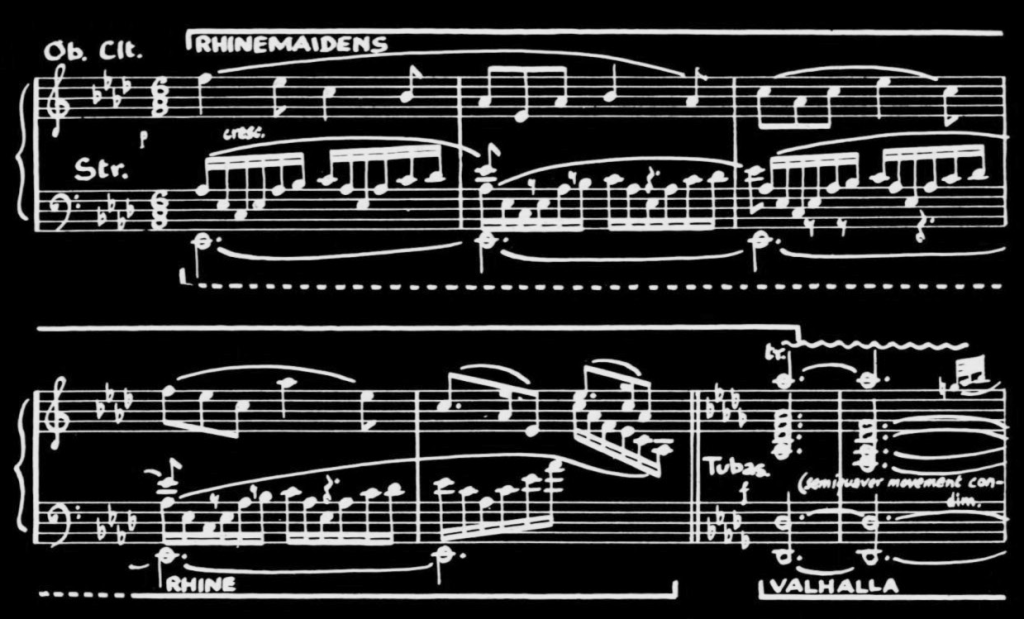

But prior to all these is the Gold, from which Alberich makes the Ring that sets the whole drama in motion. In itself it is merely a symbol of mysterious potentialities lying dormant in nature: and as we have heard, its motive belongs to the family of the Nature Motive. But the various effects of the realisation of the potentialities of the Gold are represented by a different family of motives. And the basic motive here, which generates the rest, is the salient musical idea of the joyful major-key trio sung by the Rhinemaidens in Scene One of Rhinegold – the song in which they celebrate the glory of the Gold in its natural setting. This is their cry of ‘Rhinegold, Rhinegold – Heiajaheia, Heiajaheia’.

EX. 26: THE RHINEMAIDENS’ JOY IN THE GOLD

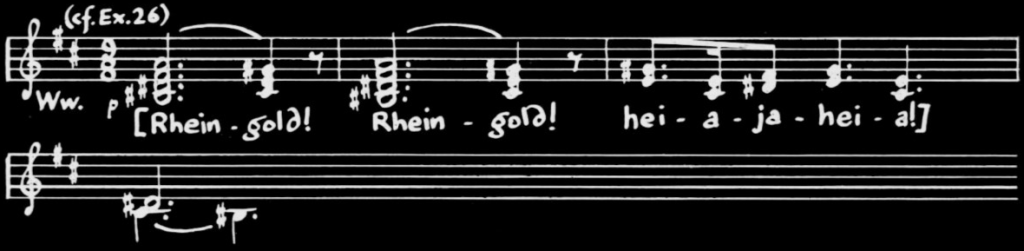

Before we trace the many transformations of this motive of the Rhinemaidens’ Joy in the Gold, we should notice that it recurs several times in something like this original form. Near the end of Rhinegold it is harmonically modified, and melodically developed, to form the Rhinemaidens’ Lament for the Gold after it has been stolen from them.

EX. 27: THE RHINEMAIDENS’ LAMENT

In this version the motive recurs again several times. In Act Two of Siegfried, for example, it enters on the horns when Siegfried comes out of Fafner’s cave holding the ring and staring at it wondering what use it can be to him. The horns remind us that it belongs ultimately to the Rhinemaidens. We will pick up the music at Alberich’s final remark and exit.

EX. 28: THE RHINEMAIDENS’ LAMENT IN ‘SIEGFRIED’

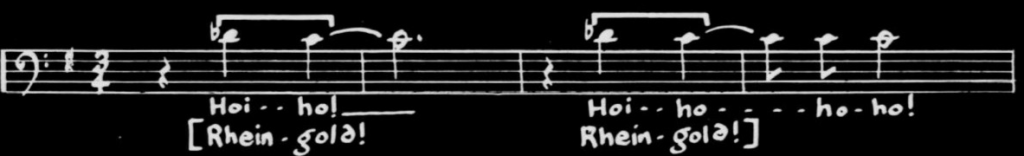

These are simply recurrences of the basic motive of the Rhinemaidens’ Joy in the Gold. But the two main segments of the motive are continually transformed into new motives, representing the unhappy results of the realisation of the gold’s potentialities. We may start with the second of these segments — the cry of ‘Heiajaheia’.

EX. 29: ‘HEIAJAHEIA!’

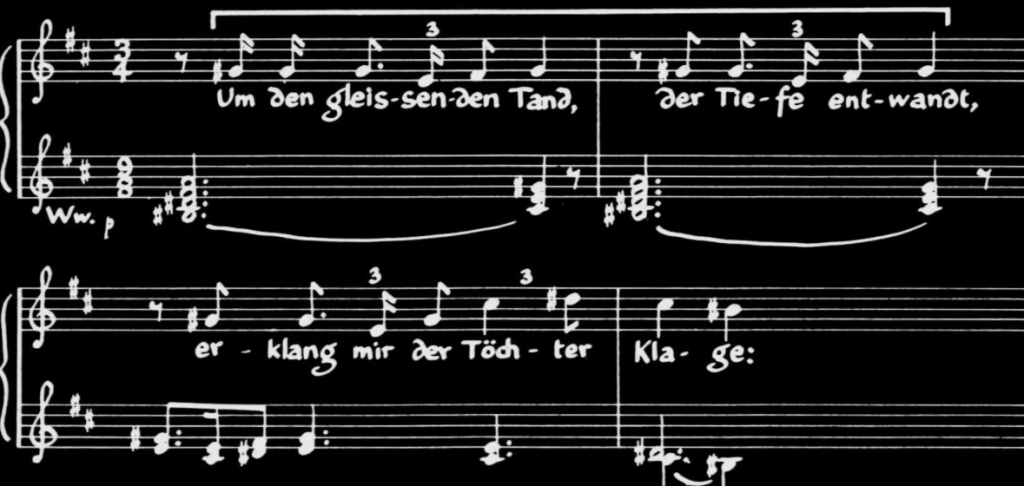

In Scene Two of Rhinegold, Loge sings a dark minor version of this when he describes how the Rhinemaidens complained to him of Alberich’s theft of the gold.

EX. 30: ‘HEIAJAHEIA’ (LOGE VERSION)

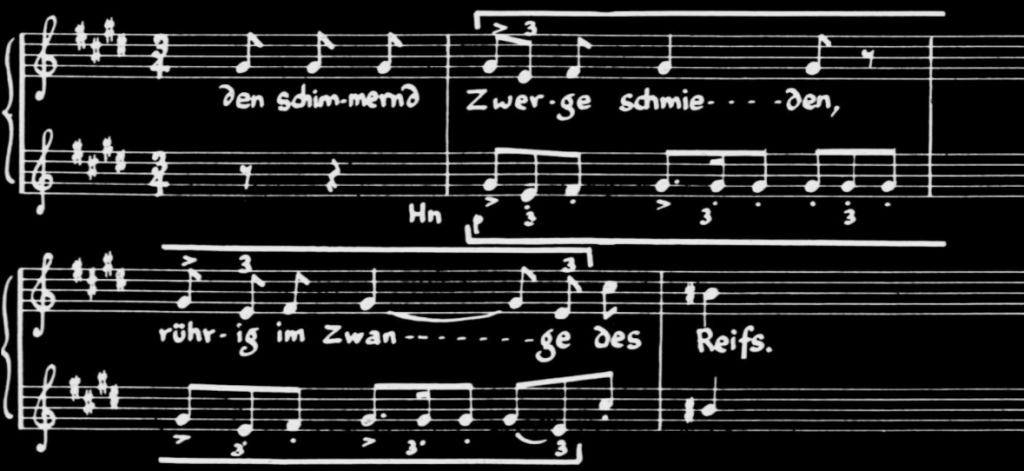

This already begins to sound a little like the Nibelungs’ Motive in the next scene, and Loge takes the transformation a step further when he repeats the music we have just heard to describe how the Nibelungs are already working on the gold.

EX. 31: ‘HEIAJAHEIA’ CHANGING TO NIBELUNGS

Loge’s embryonic version of the Nibelung Motive becomes reality in the orchestral interlude leading to the next scene. Here the actual motive of the Nibelungs emerges in its definitive form, in conjunction with the sound of their hammering.

EX. 32: THE NIBELUNGS

So the Rhinemaidens’ joy in the potentiality of the gold has been transformed into the Nibelungs’ misery in working on the gold, musically as well as dramatically. And the complete basic motive of the Rhinemaidens’ Joy in the Gold is transformed in a similar way, to produce another new motive. Again Loge is the agent of this transformation in Scene Two of Rhinegold. His dark minor version of the ‘Heiajaheia’ segment, in his account of the Rhinemaidens’ complaint, is actually accompanied by the complete motive of the Rhinemaidens’ Joy in the Gold. Here is a reminder of that motive.

THE RHINEMAIDENS’ JOY IN THE GOLD-EX. 26

And here, played by the orchestra alone, is the accompaniment to Loge’s account of the complaint of the Rhinemaidens.

EX. 33: THE RHINEMAIDENS’ JOY IN THE GOLD (LOGE VERSION)

This minor version of the Rhinemaidens’ Joy in the Gold is further slowed down and transformed harmonically to produce the baleful motive of the Power of the Ring. This enters in Scene Three and Four of Rhinegold when Alberich uses the ring to compel the Nibelungs to do his will.

EX. 34: THE POWER OF THE RING

Here, the Rhinemaidens’ Joy in the Gold has become Alberich’s sadistic pleasure in wielding the all-powerful ring he has made from the gold. One further motive is generated by the basic motive of the Rhinemaidens’ Joy in the Gold, and this too is associated with the unhappy results of the exploitation of the gold. Here, the starting point is the first segment of the motive – the cry of ‘Rhinegold’ – which we will hear again as a reminder.

EX. 35: ‘RHINEGOLD!’

A dark minor-key version of this repeated phrase is associated with the Servitude of the Nibelungs in Scene Three of Rhinegold.

EX. 36: SERVITUDE

This time the Rhinemaidens’ joy in the potentiality of the gold has become the Nibelung’s enslavement to the ring that has been made from the gold. Later, this Servitude Motive settles down to a more limping form, particularly associated with Mime in Act One of Siegfried.

EX. 37: SERVITUDE (MIME VERSION)

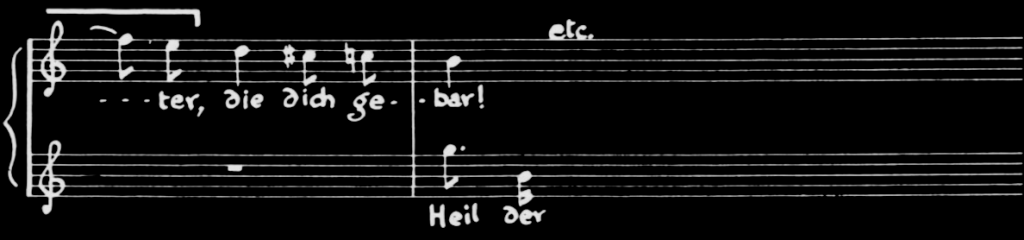

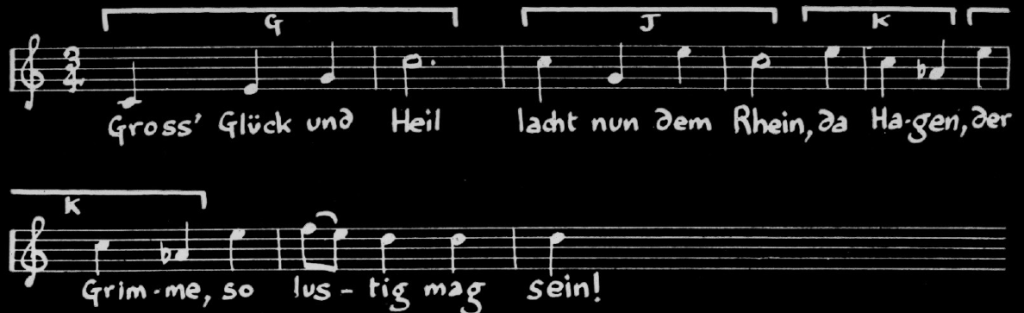

In Götterdämmerung this Servitude Motive attaches itself to Hagen, who is himself enslaved to the power of the ring through his desire to get possession of it. Here the motive takes the form of his fierce rallying-call to the Vassals in Act Two of Götterdämmerung.

EX. 38: ‘HOI-HOI!’

Here we come to the end of the dark family of motives generated by the bright basic motive of the Rhinemaidens’ Joy in the Gold.

7. The cause of the deterioration of the gold, from a life-giving inspiration to an agent of misery and death, is of course the ring of absolute power which Alberich makes from the gold and puts to such evil use.

Alberich’s ring is a central symbol of the drama – one of the two central symbols of power; and so it has its own basic motive, which enters in Scene One of Rhinegold and later generates a whole family of motives. The first, embryonic form of the Ring Motive is the undulating vocal line of the Rhinemaiden Wellgunde, in the major key, when she tells Alberich that anyone who can make a ring from the gold will be able to dominate the world.

EX. 39: THE RING (EMBRYONIC)

When Alberich reflects on Wellgunde’s words the orchestra repeats her vocal line; and then he sings a tauter version of it, in the minor key, as he soliloquizes on the possibility of absolute power.

EX. 40; THE RING (INTERMEDIATE)

This is almost the definitive form of the sinister Ring Motive, and it soon emerges clearly on clarinets and horns, near the end of the orchestral interlude leading to the next scene.

EX. 41: THE RING (DEFINITIVE)

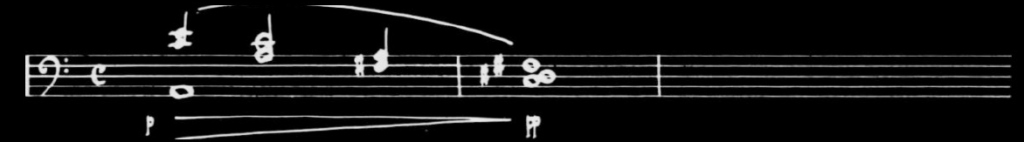

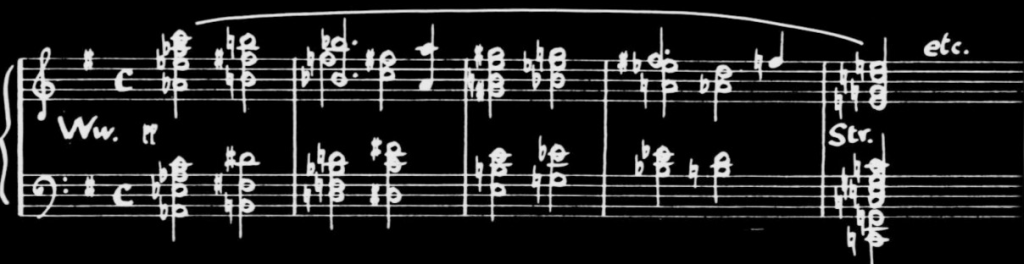

The Ring Motive is a melodic form of a chord, just as the Original Nature Motive is: but whereas the notes of the Nature Motive make up a major chord, those of the Ring Motive make up a complex chromatic dissonance in the minor key, composed of superimposed thirds. We can hear this sinister harmonic basis of the Ring Motive by means of a special illustration - the motive played by woodwind, with all its notes sustained and kept sounding as a chord.

EX. 42: THE RING (HARMONIC BASIS)

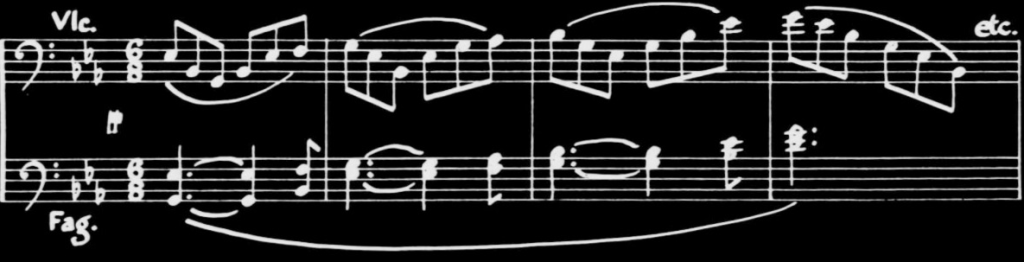

This special illustration helps us to follow the evolution of two important motives belonging to the Ring family. First the motive of Scheming, which is mainly associated with the efforts of the Nibelungs to get possession of the ring; this is a kind of groping outline of the Ring’s harmony. This can be heard from another special illustration. Here is the Ring Motive played by the cellos-pizzicato-with two bassoons holding the upper third and then falling to the lower third.

EX. 43: THE RING (OUTLINE)

The bassoons’ outline of the Ring Motive’s harmony in this special illustration is the motive of Scheming, as it appears definitively at the beginning of Siegfried in association with the plotting of Mime.

EX. 44: SCHEMING

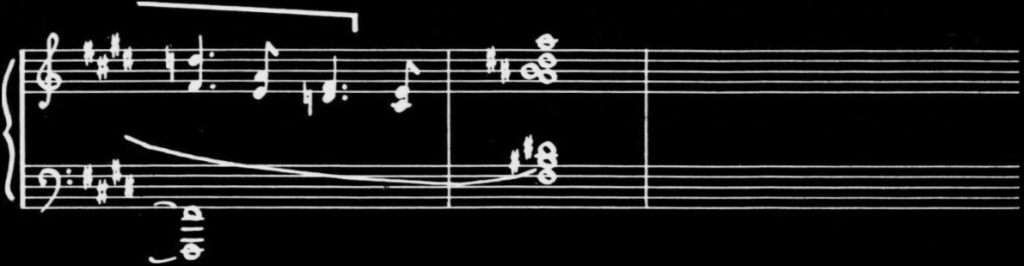

8. The other transformation of the Ring Motive’s sinister harmony is the motive of Resentment, which is introduced in Scene Four of Rhinegold, to accompany Alberich’s first bitter remarks when he is set free after having been robbed of the ring by Wotan. One further special illustration will make this clear. Here is the Ring Motive played by the clarinets with the central three notes of its harmonic basis left sounding at the end as a chord.

EX. 45: THE RING (DIMINISHED TRIAD)

This diminished triad, which lies at the heart of the Ring Motive’s sinister harmonic basis, is the starting-point for the syncopated motive of Resentment.

EX. 46: RESENTMENT

There is one further important effect of the harmonic basis of the Ring Motive which should be mentioned. This is a case, not of generating a new motive, but of generating a new form of an already existing one. The already existing one is that of the Power of the Ring, associated with Alberich in Rhinegold and later. We will hear it again as a reminder.

THE POWER OF THE RING - EX. 34

When this motive attaches itself to Hagen in Götterdämmerung it takes on a slightly different harmonic form: it now begins with a pungent dissonance.

EX. 47: THE POWER OF THE RING (HAGEN FORM)

The dissonance which begins this form of the motive is quite simply the full harmonic basis of the Ring Motive, which our first special illustration will recall to us.

THE RING (HARMONIC BASIS) – EX. 42

As can be heard, this is the exact dissonance which begins the motive of the Power of the Ring in the form associated with Hagen.

THE POWER OF THE RING (HAGEN FORM)—EX. 47

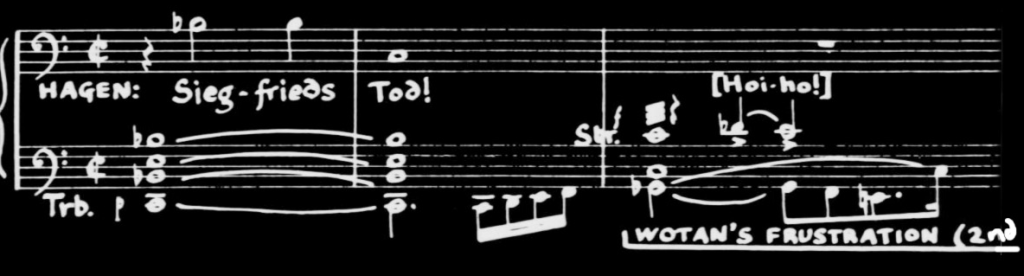

The dissonance which begins this form of the motive permeates Götterdämmerung and generates a new motive in Act Two. It acts as the starting point of the savage theme known as the motive of Murder, which is heard on the orchestra when Alberich incites Hagen to kill Siegfried and get back the ring.

EX. 48 MURDER

So this dissonance permeates Götterdämmerung, creating an atmosphere of progressive dissolution. Wagner made the sinister harmony of the Ring Motive eat its way more and more into the fabric of the score, to reflect the fact that the sinister symbol of the ring itself eats its way more and more into the fabric of the drama.

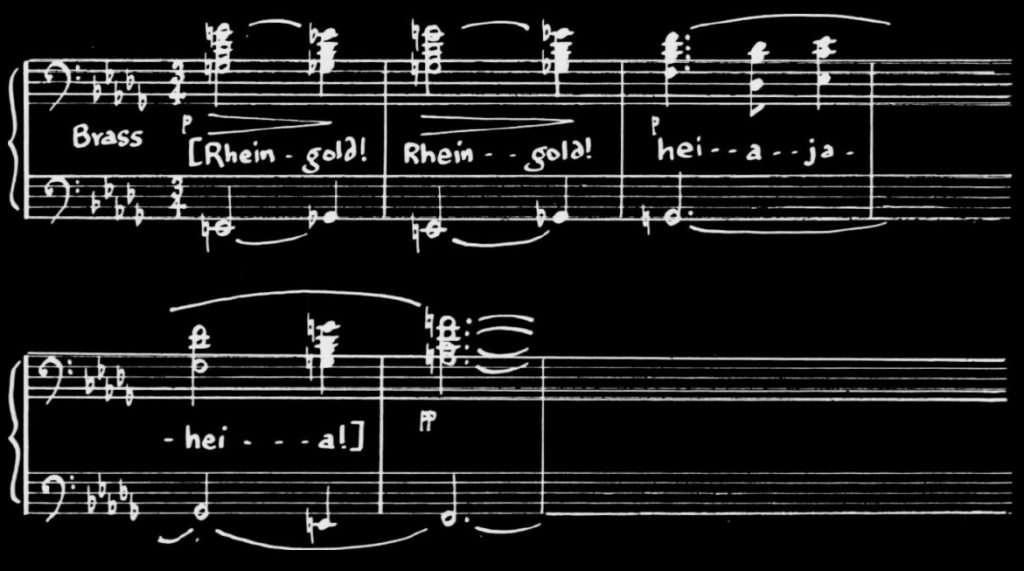

9. Several other motives, representing various aspects of the symbol of the ring, are generated by the melody of the Ring Motive. Three of these stem from its first segment of four descending notes. The most important is the motive associated with the Curse which Alberich puts on the ring in Scene Four of Rhinegold, after having been robbed of it by Wotan. Here are the first four descending notes of the Ring Motive.

EX. 49: THE RING MOTIVE (FIRST FOUR NOTES)

These four notes are turned upside down to form the menacing motive of the Curse. This is introduced vocally by Alberich, but its definitive form is established by the trombones a little later in Scene Four of Rhinegold, immediately after the first effect of the curse – the murder of Fasolt by Fafner.

EX. 50: THE CURSE

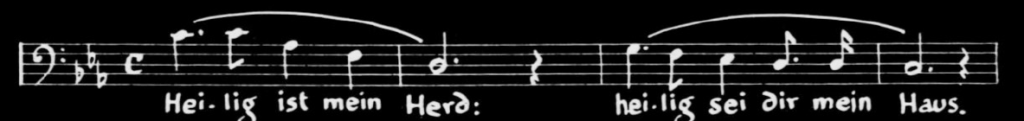

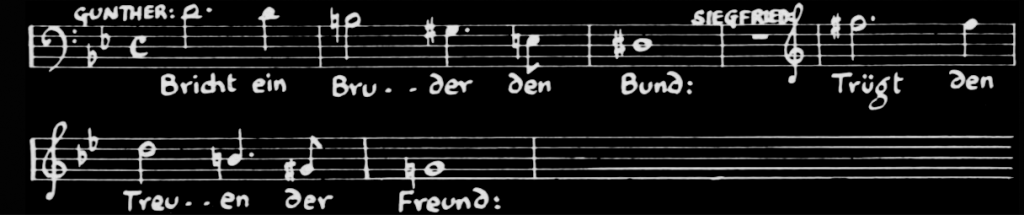

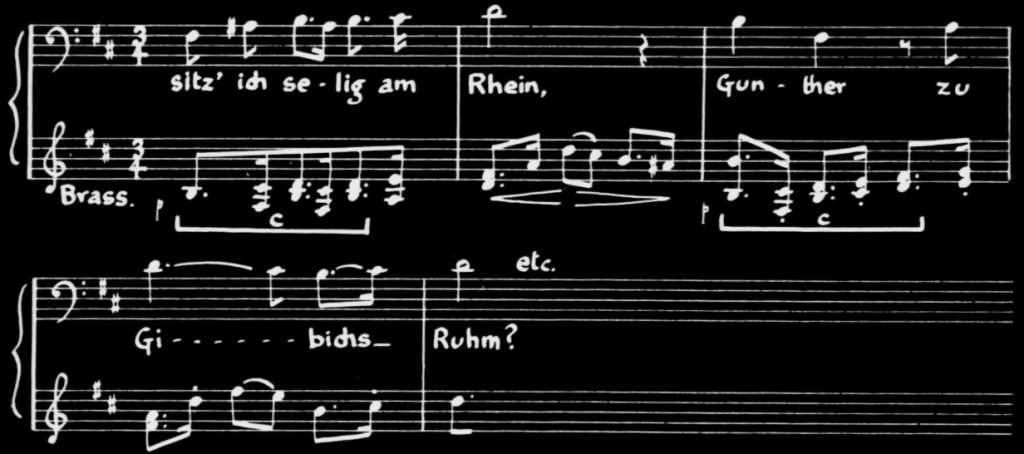

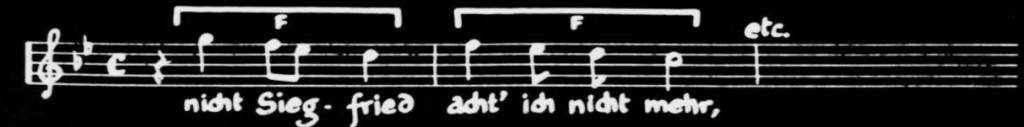

The other two motives generated from the first four notes of the Ring Motive are those of Hunding’s Rights in Walküre and the Vow of Atonement in Götterdämmerung. Hunding, if he is ignorant of the existence of the actual ring, is nevertheless a wielder of the kind of ruthless power it symbolises: and as for the Vow of Atonement, which forms part of the oath of blood-brotherhood sworn by Siegfried and Gunther, the significance of the ring-shaped motive here is one of tragic irony.

Through the vow Siegfried puts himself entirely in the power of Hagen, who uses it as a pretext for murdering him to get possession of the ring. Both these motives are direct transformations of the first four notes of the Ring Motive, which we will hear again now.

THE RING MOTIVE (FIRST FOUR NOTES)—EX. 49

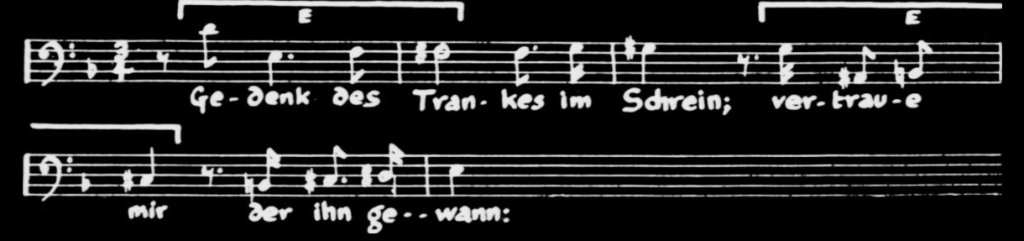

Now here is the stern motive of Hunding’s Rights, which is introduced vocally by Hunding himself to the words – ‘Sacred is my hearth: Sacred to you be my home’.

EX. 51: HUNDING’S RIGHTS

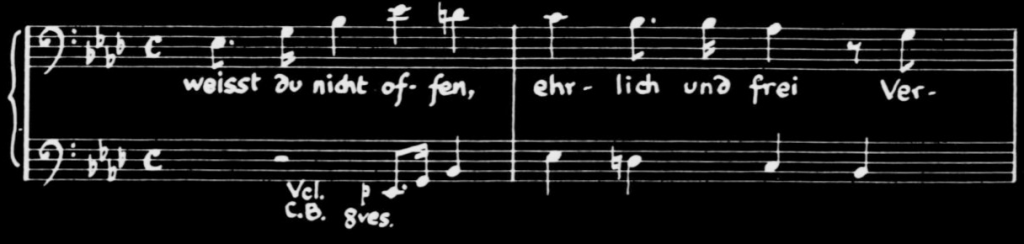

And here is the tragic motive of the Vow of Atonement, as introduced by Gunther

and Siegfried in Act One of Götterdämmerung.

EX. 52: THE VOW OF ATONEMENT

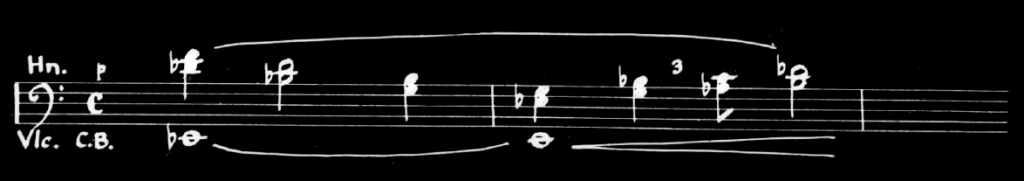

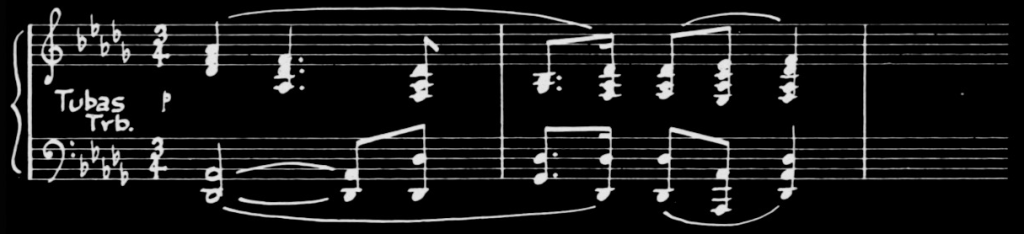

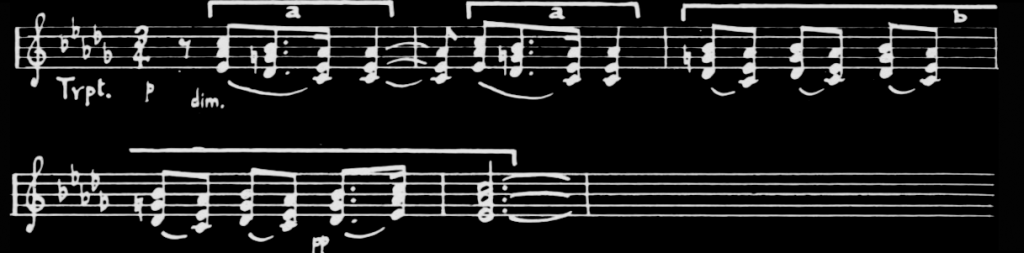

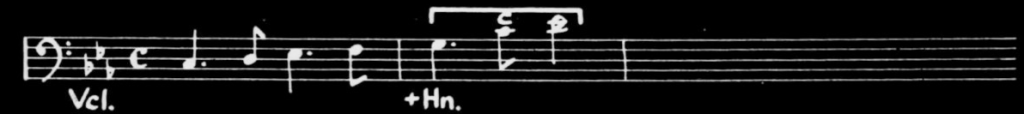

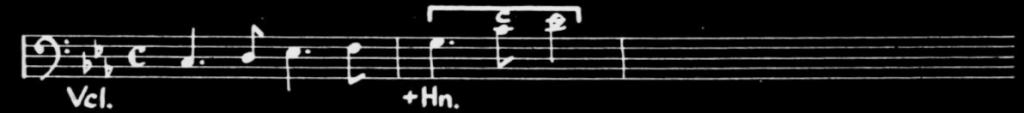

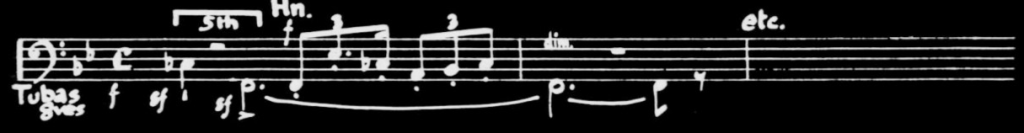

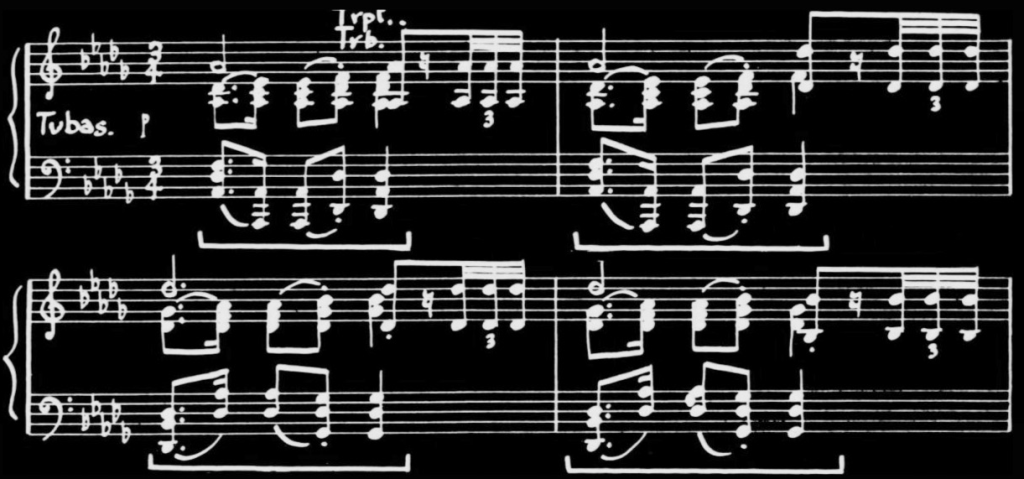

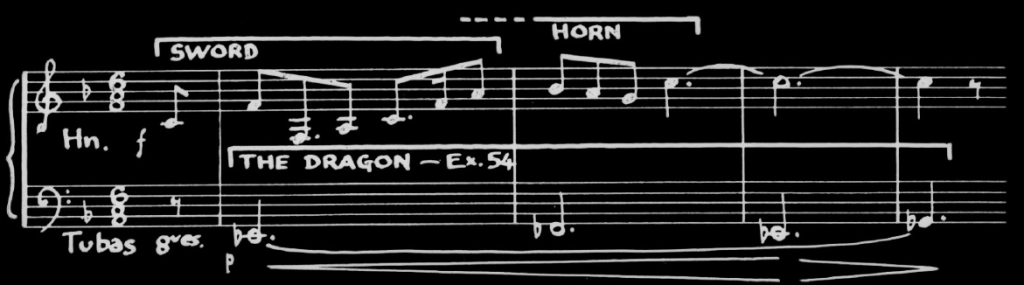

10. Two further motives are evolved from the other segment of the Ring Motive - its last three rising notes. Both enter in Scene Three of Rhinegold: the first is that of the Hoard of Treasure, which appears when Alberich tells Wotan about the Hoard, and how he will use it to make himself master of the world.

The second is that of the Dragon, which enters when Alberich transforms himself into a huge serpent, ostensibly to demonstrate the powers of the Tarnhelm, but really to warn Wotan and Loge of his power to guard the ring and the hoard. Both motives are built out of repetitions of the rising third which ends the Ring Motive, a note higher each time; and both are given to the tubas to suggest some monstrous evil rising from the depths to engulf the world. Here is the Ring Motive again as a reminder.

THE RING—EX. 41

The last three notes of the Ring Motive repeated over and over by the tubas, generate the motive of the Hoard. Here it is as it occurs definitively in the Prelude to Siegfried with the Servitude Motive repeated above it.

EX. 53: THE HOARD

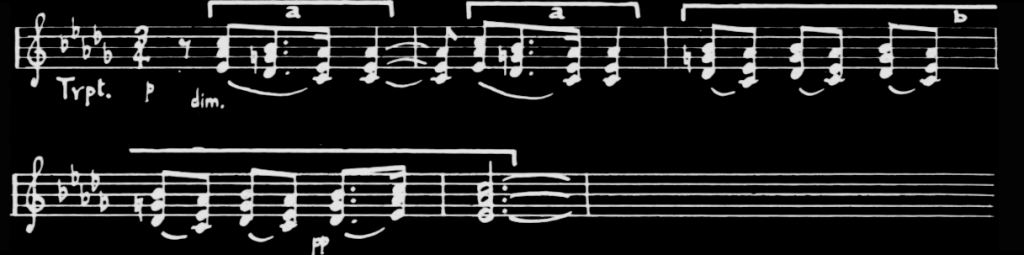

The motive of the Dragon is a rather freer development of the last three notes of the Ring Motive: but again it consists of repetitions by the tubas of a phrase revolving round a third, each repetition a note higher than the one before.

EX. 54: THE DRAGON

This Dragon Motive later takes on a slightly different form, on solo tuba, to represent Fafner in Act Two of Siegfried, when he has turned himself into a Dragon to guard the ring and the hoard.

EX. 55: FAFNER AS DRAGON

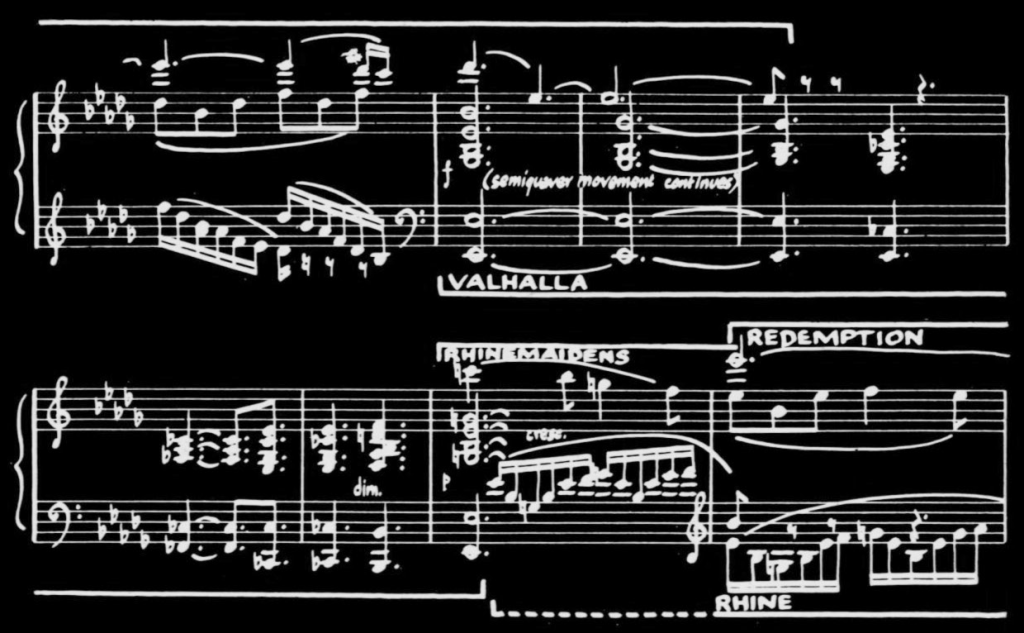

This is the last of the dark family of motives generated by the basic power-motive of The Ring. But there is one separate, bright transformation of the Ring Motive — the first and simplest of all: this emerges soon after the motive has found its definitive form in the orchestral interlude leading from Scene One of Rhinegold to Scene Two. Eventually the newly established Ring Motive begins to take on a less inimical form; its sinister harmonic basic becomes much more genial on the horns.

EX. 56: THE RING (CHANGING TO VALHALLA)

Immediately after this, at the very beginning of Scene Two, the Ring Motive changes its harmonic basis a little further to simple major harmonies; and in so doing it transforms itself into the majestic brass motive to be associated with Wotan’s castle – Valhalla.

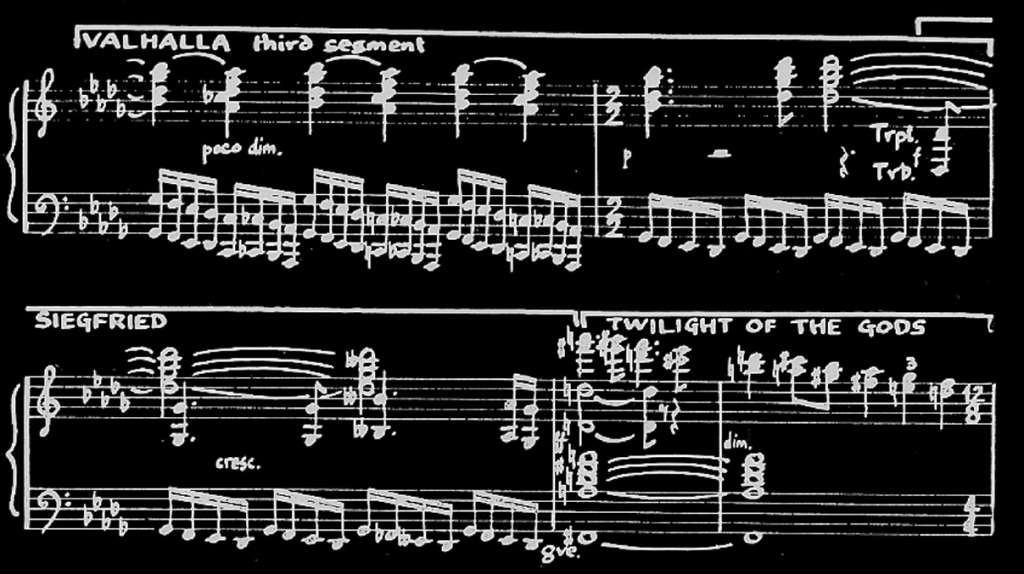

EX. 57: VALHALLA (FIRST SEGMENT)

The melodic similarity between the Valhalla Motive and the Ring Motive establishes the near-identity of the ultimate aims of Alberich and Wotan - absolute power in each case; and the harmonic contrast between them expresses the much nobler character of Wotan’s conception of absolute power compared with Alberich’s.

But the phrase we have just heard is only the first segment of the Valhalla Motive, though the most important one: there are other segments which are also to recur on their own. Two of these soon follow the first one: a repeated falling phrase and a series of alternating chords.

EX. 58: VALHALLA (2nd and 3rd SEGMENTS)

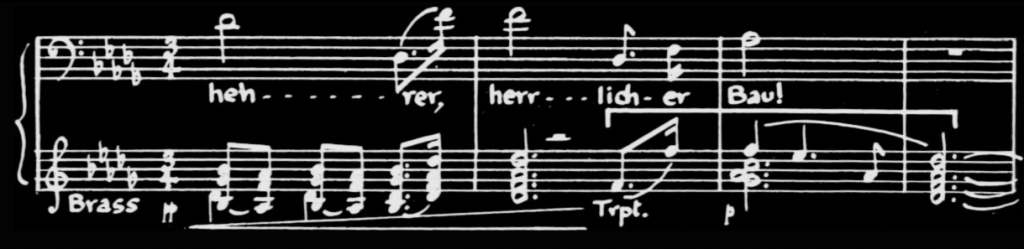

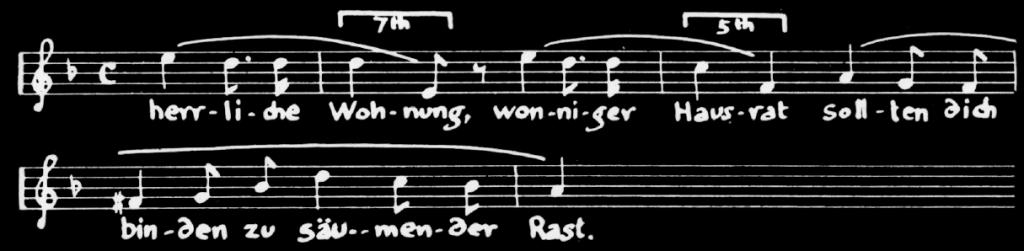

The final segment of the Valhalla Motive, which is a kind of summing-up of its noble character, does not enter until the end of Wotan’s actual apostrophe to Valhalla itself. It appears on the trumpet at the words – ‘Noble, splendid fortress’.

EX. 59: VALHALLA (FINAL SEGMENT)

We can hear this final segment of the Valhalla Motive more clearly by having the passage played by the orchestra alone.

EX. 60: VALHALLA (FINAL SEGMENT)

This final segment of the Valhalla Motive also occurs frequently on its own. It has a habit of attaching itself to the ends of other motives as a cadence. For example, when Wotan conceives the idea of the Sword in Scene Four of Rhinegold it rounds off the trumpet’s Sword Motive with the effect of setting a seal of majesty on the new conception.

EX. 61: THE SWORD WITH VALHALLA FINAL SEGMENT

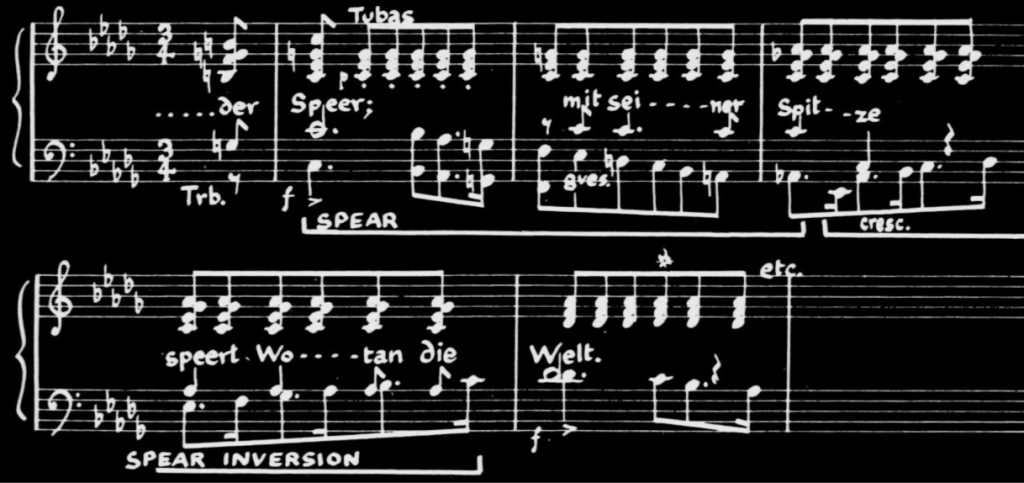

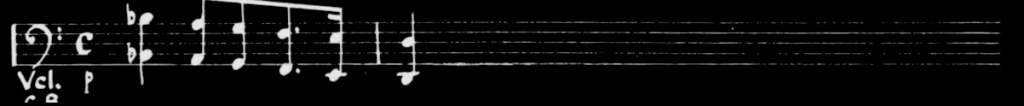

Although the complete Valhalla Motive and its various segments recur throughout the whole work, the motive does not generate a family of motives. This is because Wotan’s castle is only a static symbol of his power, not a dynamic symbol of the agency of his power, akin to Alberich’s ring. The agency of Wotan’s power is his spear: this is the other central power-symbol of the drama, and it has its own basic motive, which does generate a whole family of motives.

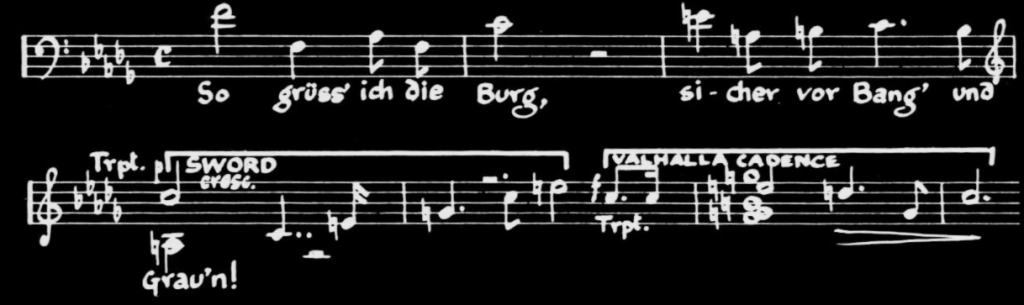

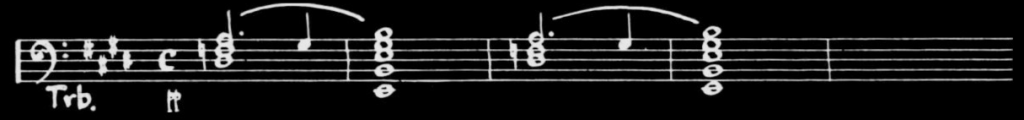

11. The basic motive associated with the spear has always been labelled the ‘Treaty’ or ‘Bargain’ motive, because Wotan’s power resides in the treaties sworn on the spear and engraved on it. But these treaties, which are actually the laws whereby Wotan governs the world, are only maintained by his will, and this is what the power of the spear represents.

Wotan’s spear is the symbol of his will towards uncontrolled, unlawful world-domination, just as Alberich’s ring is the symbol of his will towards uncontrolled, unlawful world-domination. And so the basic power- motive associated with the spear should take the name of the symbol itself, just as the basic power-motive associated with the ring is called the Ring Motive.

The Spear Motive, which is a stern descending minor scale, first appears in Scene Two of Rhinegold. It enters quietly in the bass when Fricka reminds Wotan that he will have to fulfil his contract with the Giants and give them the promised payment for building Valhalla – the goddess Freia.

EX. 62: THE SPEAR (FIRST VERSION)

Later in the same scene, when Donner lifts his hammer to crush the Giants, Wotan stretches out his spear and imposes the law by the main force of his will; and here the definitive form of the Spear Motive, beginning on a strong beat, enters powerfully on the trombones.

EX. 63: THE SPEAR (DEFINITIVE)

Before considering the family of motives generated by this, main Spear Motive we should notice that it has another segment, concerned specifically with the irrevocable character of the treaties sworn on the spear. This is introduced vocally by Fasolt when he warns Wotan that he must keep faith.

EX. 64: IRREVOCABLE LAW

Before considering the family of motives generated by the descending scale of the main Spear Motive is a subsidiary one which represents Wotan’s actual contract with the Giants. This is the real Treaty Motive: Fasolt introduces it vocally, echoed by the cellos and basses, when he warns Wotan to fulfil the contract.

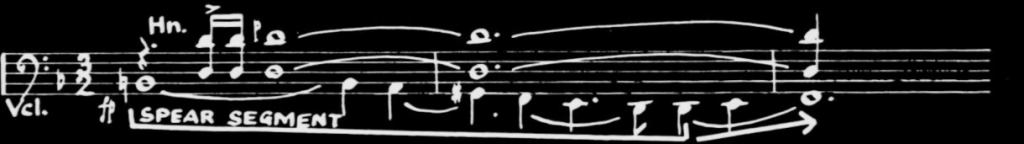

A more important transformation of the Spear Motive follows immediately. This is the embryonic form of the majestic motive of the Power of the Gods, which should perhaps be called the Power of Wotan.

When Fasolt goes on to warn Wotan that his whole power resides in the laws engraved on the spear, the Spear Motive enters in the bass below a series of pulsating chords. This is the embryonic form of the motive of the Power of the Gods.

EX. 66: THE POWER OF THE GODS (EMBRYONIC)

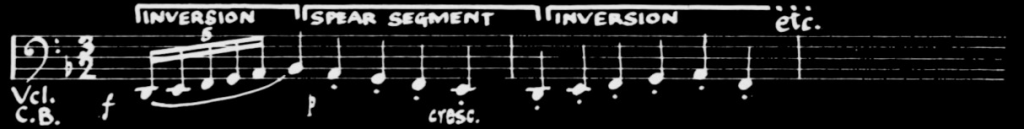

An intermediate form of this motive enters on the orchestra in Act One of Siegfried when Wotan tells Mime how he rules the world with the spear which he cut from the World Ash-Tree. This time, underneath the pulsating chords, the descending scale of the Spear Motive alternates with its inversion – a rising scale.

EX. 67: THE POWER OF THE GODS (INTERMEDIATE)

In Götterdämmerung the rising scale detaches itself from the descending one to become the definitive form of the motive of the Power of the Gods. This enters during the Norns’ scene in the Prelude: but it rises to its full strength in the final scene of the work, when Brünnhilde orders the funeral pyre to be built for Siegfried, which will finally bring the power of the gods to an end.

EX. 68: THE POWER OF THE GODS (DEFINITIVE)

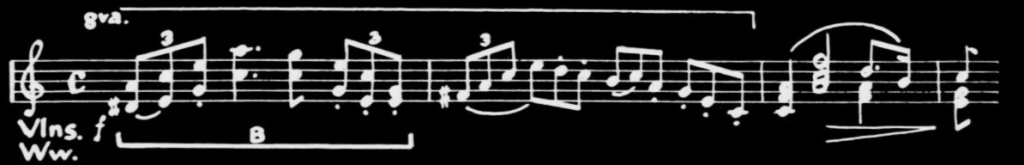

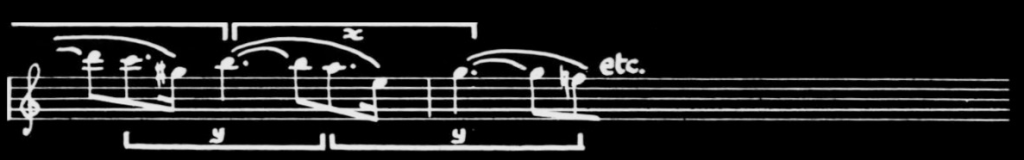

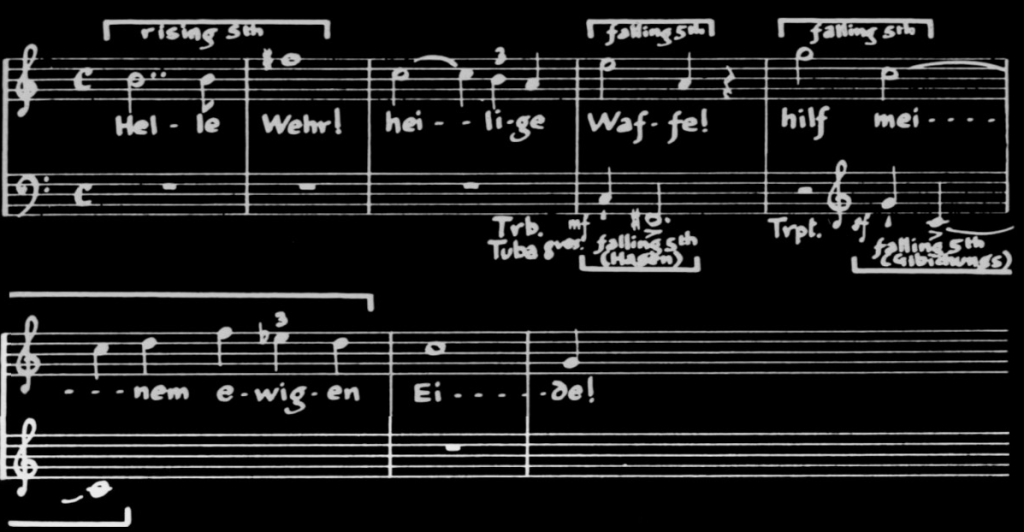

12. Along another, more complex line of transformation the Spear Motive continually generates new motives throughout Walküre. These are derived from the opening six-note segment of the Spear Motive: they are those of the Storm, and of Siegmund — Wotan’s son and unwitting agent, who at the beginning of Walküre is running through the storm for his life.

In each of these motives the descending scale-motion of the complete Spear Motive is checked and opposed; after the first descending six-note segment a rising motion contradicts it. Indeed, throughout Walküre the repressive authority of Wotan’s will is to be continually challenged by the other characters, and eventually neutralised.

Here first of all is another special illustration presenting the first descending six- note segment of the Spear Motive.

EX. 69: THE SPEAR (FIRST SEGMENT)

Now here is the Storm Motive. It consists of the first descending six-note segment of the Spear Motive played swiftly, in alternation with its inversion—the same notes rising upwards.

EX. 70: THE STORM

Out of the Storm Motive emerges the very similar motive of Siegmund, who is to rebel against Wotan’s authority. This also enters in the bass; and again the first descending segment of the Spear Motive is checked and contradicted by a rising motion.

EX. 71: SIEGMUND

A little later, in Act One of Walküre, Siegmund’s falling and rising motive is joined by the rising and falling one of Sieglinde: as the mood grows more tender the upward motion, contradicting the Spear Motive’s descent, grows stronger.

EX. 72: SIEGMUND AND SIEGLINDE

13. In Act Two of Walküre Wotan’s authority is effectively thwarted by Fricka, who argues him into abandoning Siegmund, and the plan of which Siegmund is the unwitting agent. The gloomy motive associated with Wotan here is generally known as ‘Discouragement’: but it might be called ‘The Frustration of Wotan’s Will’, since it is a twisted form of the first descending six-note segment of the Spear Motive. Here is the segment again as a reminder.

THE SPEAR (FIRST SEGMENT) – EX.69

This segment, ireeiy transiormea, generates the motive or Wotan’s Frustration. The motive begins with a little turn, twisting moodily around the first note; and not only is the descending motion opposed by a rising one, but it is also hindered by being turned around on itself.

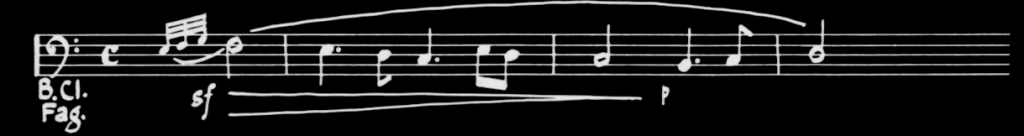

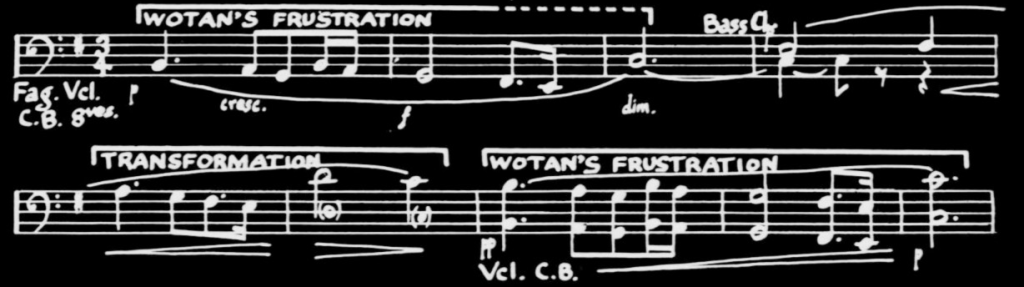

EX. 73: WOTAN’S FRUSTRATION

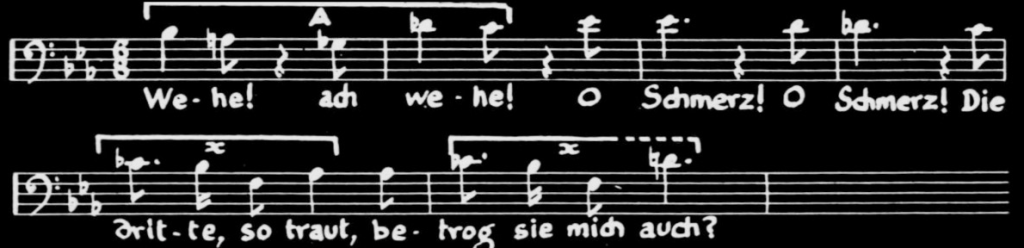

Incidentally, this motive, like several others, takes on a new form in Götterdämmerung. The tragic happenings in that work are felt to be at least partly the result of Wotan’s change of mind after his humiliation by Siegfried.

His sense of frustration, which disappears in the opera Siegfried, returns in Götterdämmerung and grows more acute, as we learn from Waltraute; and this is expressed by a new leaping and falling form of the motive of his frustration. We hear it in the orchestra after Waltraute has told Brünnhilde of Wotan’s indifference to everything except the idea of restoring the gold to the Rhinemaidens.

EX. 74: WOTAN’S FRUSTRATION (SECOND FORM)

This motive recurs many times in Götterdämmerung especially in conjunction with Hagen’s plotting to destroy Siegfried, since this act will set in motion the series of events that is to lead to the restoration of the gold to the Rhinemaidens.

EX. 75: WOTAN’S FRUSTRATION (HAGEN FORM)

14. Returning now to Act Two of Walküre – after Fricka’s exit, Wotan rages against her thwarting of his will, and here the motive of his frustration is inverted, moving upwards instead of downwards. Moreover, it moves straight upwards without convolutions: and in doing so it generates the furious motive of Wotan’s Revolt, which is thus a free inversion of the whole original Spear Motive. It always merges into the motive of the Curse, as here, on its first appearance.

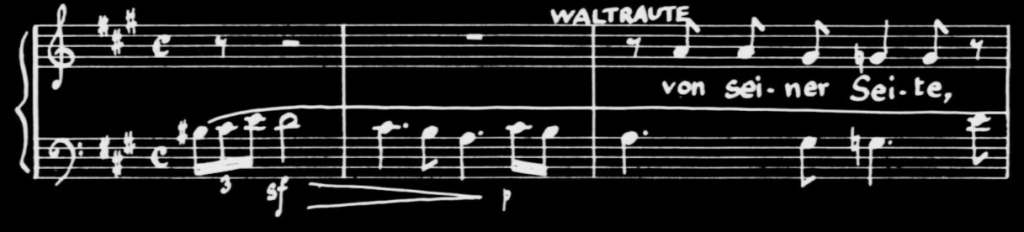

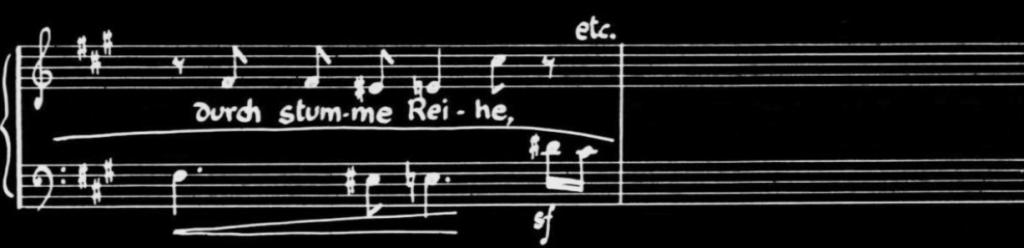

In Act Three of Walküre the twisted motive of Wotan’s Frustration evolves gradually into the motive associated with Brünnhilde’s rebellion against him — the motive of the Reproach she addresses to him. At the beginning of this scene we hear the transformation take place; the motive of Wotan’s Frustration on the bass strings is answered by a free transformation of it on the bass clarinet, in which the descending motion of the original Spear Motive is now opposed by a wide leap to the upper octave.

EX. 77: WOTAN’S FRUSTRATION/BRÜNNHILDE’S REPROACH

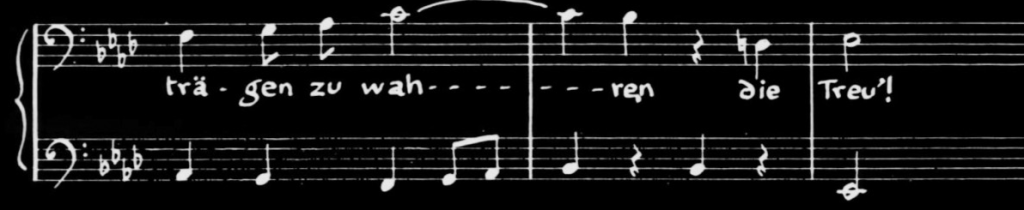

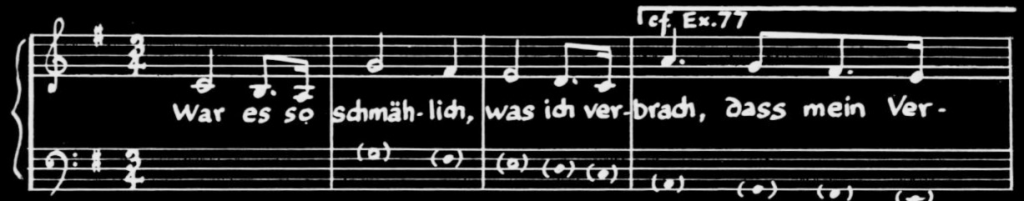

This bass clarinet phrase is taken up by Brünnhilde as she reproaches Wotan for condemning her disobedience-her attempt to carry out his original plan, which she knew he had countermanded in spite of his deepest wishes. Her Reproach motive presents the full descending scale of the Spear Motive, continually opposed by leaps to the upper octave.

EX. 78: BRÜNNHILDE’S REPROACH

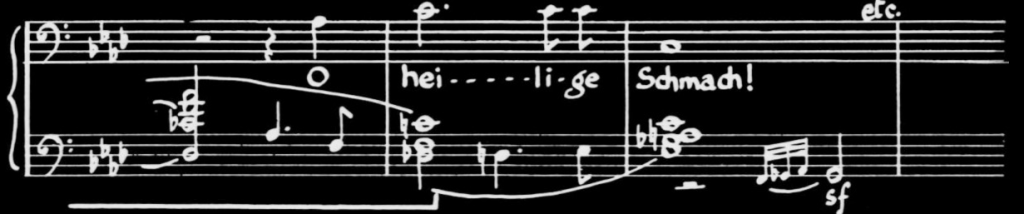

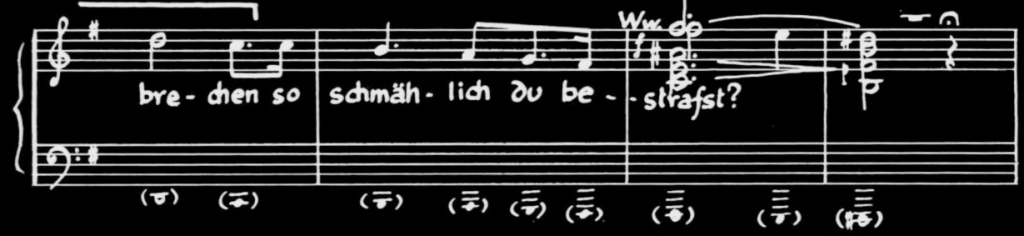

Later on in the Third Act this motive of Brunnhilde’s Reproach turns to the major, to become a new motive representing the positive symbol she is opposing to the authority of Wotan’s Spear – compassionate love. The motive enters on the orchestra as Brünnhilde tells Wotan that what has made her defy his orders was the feeling of love which he himself had breathed into her, and which had been awakened by her realisation of Siegmund’s love for Sieglinde.

EX. 79: BRUNNHILDE’S COMPASSIONATE LOVE

So the repressive descending minor scale of the Spear Motive is finally transformed into the expansive, soaring motive associated with Brünnhilde’s compassionate love: and this is the last of the family of motives generated by the basic motive of the Spear.

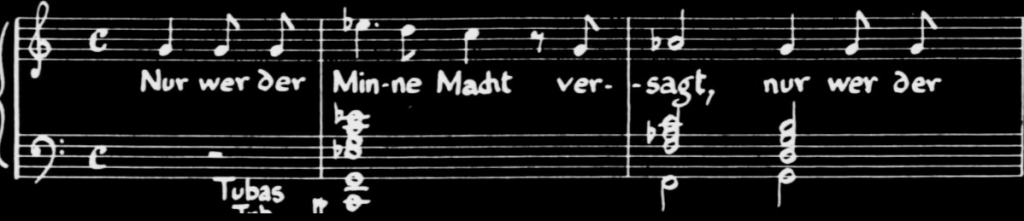

15. Love is another of the central symbols of the drama, standing in direct opposition to the two central symbols of power – the Ring and the Spear. In the first place it naturally stands in opposition to the ring because the crucial condition attached to the making of the ring is the renunciation of love.

And this condition has its own motive-a tragic one in the minor key. It enters in Scene One of Rhinegold; it is sung by the Rhinemaiden Woglinde, when she tells Alberich that only the man who is prepared to renounce love can make the ring from the gold.

EX. 80: RENUNCIATION OF LOVE

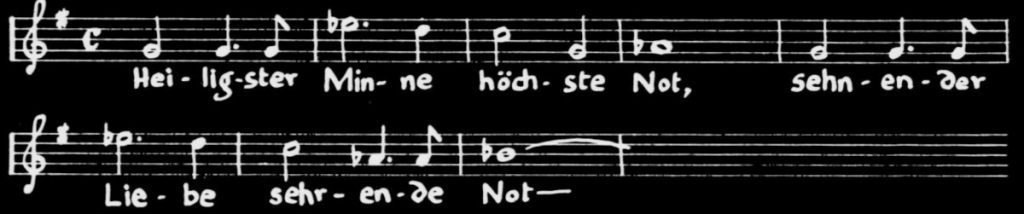

This motive of the Renunciation of Love recurs at various points in the drama - most surprisingly perhaps, in Act One of Walküre. Siegmund sings it as he draws the sword from the tree – the decisive action which proclaims his identity as the brother of Sieglinde, and her true lover.

EX. 81: RENUNCIATION OF LOVE (SIEGMUND VERSION)

Ring has begun in a world without love; and this is symbolised by the Renunciation Motive. The claims of love only begin to assert themselves in Act One of Walküre, and they are only established in Act Three in the compassionate love of Brünnhilde, represented by the motive we heard a little earlier.

Wotan himself, in his own way, has renounced love as decisively as Alberich, by offering Freia, the goddess of love, as a wage to the Giants for building Valhalla. And so the Renunciation Motive is also associated with him, though in a different form.

This stems from the second of the two phrases in the original motive: and the agent of transformation is Fricka in Scene Two of Rhinegold, when she tells Wotan that his bartering away of Freia shows his contempt for love. Flere is the second phrase of the Renunciation Motive as sung originally by Woglinde.

EX. 82: RENUNCIATION OF LOVE (2ND SEGMENT)

When Fricka accuses Wotan of despising love, the orchestra plays the first phrase of the Renunciation Motive, but her utterance ends by hinting harmonically at this second one.

EX. 83: RENUNCIATION OF LOVE (CHANGING TO 2ND FORM)

16. Later in the same scene Loge acts as the final agent of transformation, when he says that in all the world he has been unable to find anything valuable enough to serve as a substitute wage for the Giants, instead of the goddess of love, Freia. Here he adapts the phrase of Fricka, which we have just heard, into the second form of the Renunciation Motive which is to be associated with Wotan, and later with other characters.

EX. 84: RENUNCIATION OF LOVE (2ND FORM)

This second form of the Renunciation Motive often recurs as a mournful cadence, expressing futility. One of the many examples is to be found in Act Two of Walküre when Wotan, having realised his own lovelessness, describes himself as the unhappiest of men. Here is the whole passage leading up to the use of the Renunciation Motive as a cadence.

EX. 85: RENUNCIATION MOTIVE (2ND FORM. WITH WOTAN)

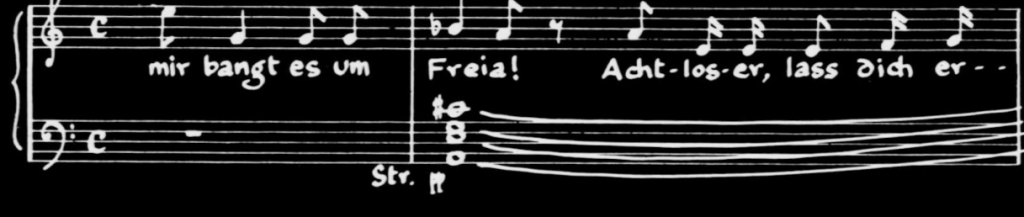

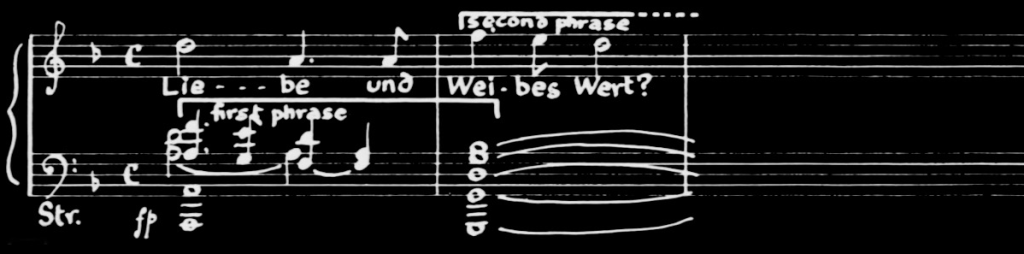

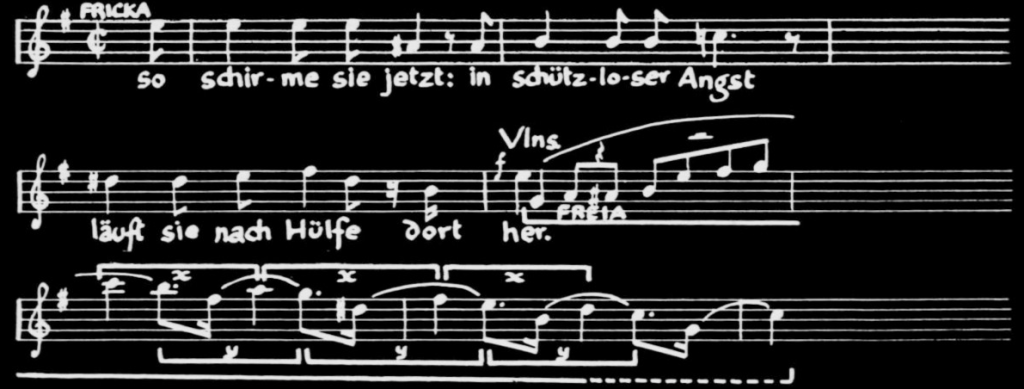

But the Renunciation Motive, in both its forms, only represents love in a negative light: it stands for the general lovelessness prevailing in the power-ridden world of the drama. The basic love-motive — the positive, dynamic motive of love in action, in opposition to absolute power- is the one associated with the central symbol of love in the drama: the goddess of love herself, Freia. Her motive first enters on the orchestra in Scene Two of Rhinegold, when she runs on, pursued by the Giants. Fricka describes her approach, and as Freia enters her motive is introduced in the violins.

EX. 86: FREIA

We can hear Freia’s swift motive more clearly from another special illustration — the violin part played on its own, a little more slowly.

EX. 87: FREIA (VIOLINS)

17. Freia’s Motive has two independent segments; we may begin by considering the first – the rising one.

EX. 88: FREIA (FIRST SEGMENT)

This first segment of Freia’s Motive is swift here, and in the minor, to portray Freia’s agitation as she flees from the Giants: but it soon establishes its definitive, slow major form. This stands out clearly for the first time when it introduces Loge’s ‘hymn to love’ a little further on in the same scene.

EX. 89: FREIA (FIRST SEGMENT – DEFINITIVE)

This definitive, sinuous form of the first segment of Freia’s Motive recurs on its own throughout The Ring, in association with the sensuous aspect of love between man and woman. For example, in Act One of Walküre, after Siegmund’s first fully impassioned utterance to Sieglinde, it ascends sweetly on the violins.

EX. 90: FREIA (FIRST SEGMENT, SIEGMUND AND SIEGLINDE)

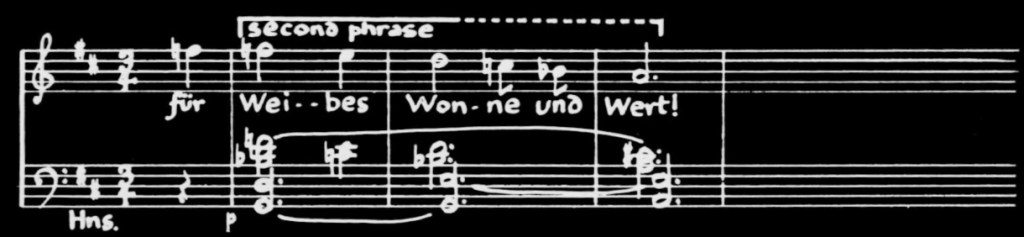

No new motives are generated from this first segment of Freia’s Motive – it remains itself throughout The Ring. The whole family of motives representing the various aspects of love is generated by the second segment of her motive, which we will recall now.

EX. 91: FREIA (SECOND SEGMENT

This second segment of Freia’s Motive was identified wrongly by the very first commentator on The Ring – Hans von Wolzogen. He labelled it ‘Flight’, and every commentator since has followed him unthinkingly. The whole motive enters in conjunction with Freia, and as with many other motives its segments apply equally to the symbol it is attached to: it was not Wagner’s practice to detach segments of his motives from the symbols they are initially associated with, and give them quite different meanings.

18. The label ‘Flight’ might at times seem to be justified, since the segment does recur in something like its original form when various characters are in flight. For example, it portrays Siegmund and Sieglinde fleeing from Hunding in the Prelude to Act Two of Walküre.

EX. 92: ‘FLIGHT’

However, the characters in flight here — Siegmund and Sieglinde — are symbols of love, as Freia herself is, even when fleeing from the Giants. And if we examine this second segment of Freia’s Motive we find that it functions exactly like the first segment, as a love motive. In conjunction with the first segment it soon establishes a definitive, slow major form. Here is the original Freia Motive again, complete.

FREIA (VIOLINS)—EX. 87

19. When Fasolt, in Scene Two of Rhinegold, explains to Wotan that he looks forward to having Freia as a wife in his home, the oboe accompanies his vocal line with the whole of Freia’s Motive, both first and second segments, in the definitive, slow major form.

EX. 93: FREIA COMPLETE (DEFINITIVE)

And the second segment of Freia’s Motive, in exactly the same way as the first, detaches itself in its definitive, slow major form and recurs as a pure love-motive in association with Siegmund and Sieglinde in Act One of Walküre. Here is the second segment again, in its original swift minor form.

When Siegmund drinks the mead which Sieglinde has brought him, and they stare into one another’s eyes and fall in love, this second segment of Freia’s Motive enters in its definitive, slow major form as their basic love-motive.

EX. 94: FREIA (2ND SEGMENT. SIEGMUND AND SIEGLINDE)

This basic love-motive represents the compassionate aspect of love as opposed to its sensuous aspect, which is expressed by the first segment of Freia’s Motive. It recurs in many different forms: two main ones are slow and in the major, as here, and swift and in the minor, as at first, to represent love being driven out and pursued - hence the mistaken label of ‘Flight’.

There are certain passages where the swift minor form of the motive might seem to imply flight, or at least pursuit, devoid of any associations with love; but these have been misunderstood. An example is the descent of Wotan and Loge to Nibelheim between Scenes Two and Three of Rhinegold. Here, the second segment of Freia’s Motive is repeated over and over, very swiftly in the minor; and the suggestion is that Wotan and Loge are in flight in some abstruse sense, or at least that they are in swift pursuit of Alberich and the ring.

EX. 95: ‘FLIGHT’ IN THE ‘DESCENT TO NIBELHEIM’

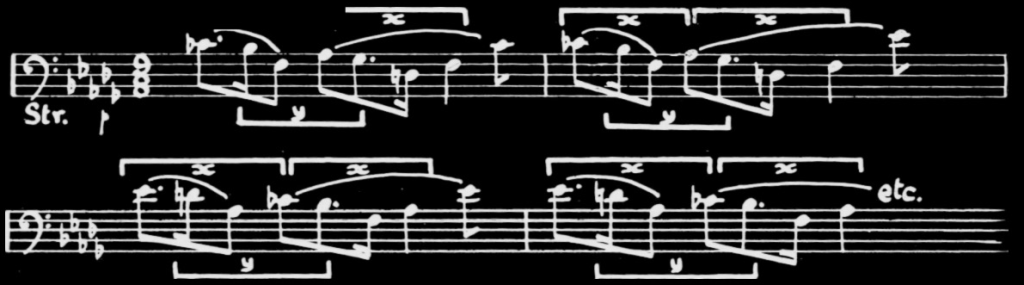

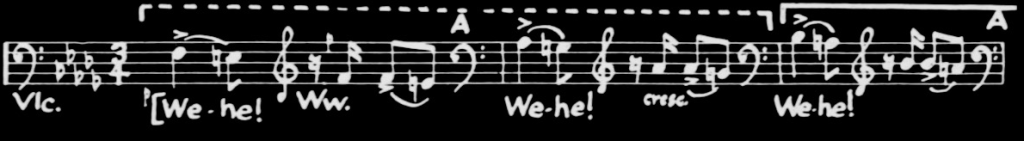

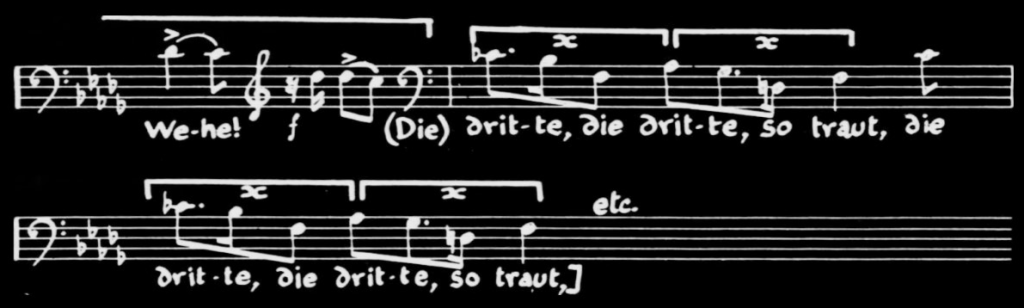

To understand the true significance of this passage we have to realise that the origin of this second segment of Freia’s Motive-the basic love-motive-goes back beyond Freia herself to Scene One of Rhinegold. Here a short, embryonic form of it is introduced in association with the thwarting of Alberich’s passion by the Rhinemaidens.

When Alberich is finally rejected by the third Rhinemaiden – Flosshilde – he introduces this embryonic form of the basic love-motive, rather slowly and in the minor, to express his grief over the frustration of his wooing.

EX. 96: FREIA (2ND SEGMENT, ALBERICH)

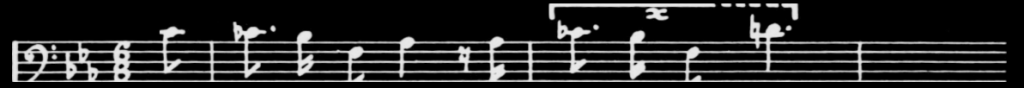

It is this short embryonic version of the basic love-motive which is developed in the Descent to Nibelheim. To make this absolutely clear let us hear Alberich’s lament in Scene One again, picking up the music a little earlier, beginning with his cries of ‘Woe is me’ which lead to his embryonic version of the basic love-motive.

EX. 97: ALBERICH’S LAMENT

The Descent to Nibelheim takes this passage as its starting-point. It re-states Alberich’s cries of ‘Woe is me’ more quickly, and then it develops his short embryonic version of the love-motive furiously, in a way made possible by the definitive continuous form of it, now associated with Freia.

EX. 98: FREIA SECOND SEGMENT/DECENT TO NIBELHEIM

It is clear that when this passage begins, just after the music associated with Loge in Scene Two, Wagner employs a flash-back technique, which he often uses’ in orchestral interludes. He turns away from Wotan and Loge, and their descent to Nibelheim, and picks up Alberich on his descent to Nibelheim, from the Rhine, after Scene One.

Alberich’s thwarted desire for love has turned bitter, and is being transformed into a fierce lust for power — a familiar psychological phenomenon which is the true underlying meaning of the dependence of absolute power on the renunciation of love.

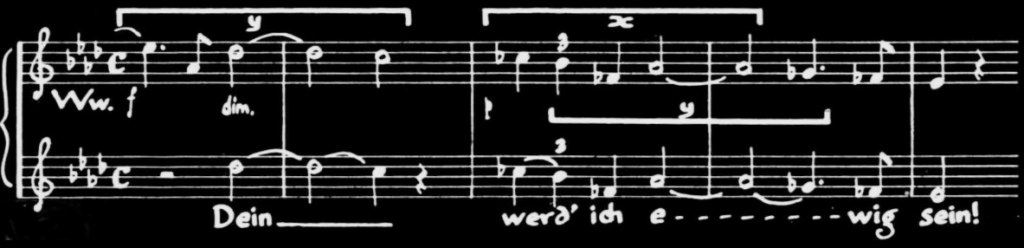

20. A little later in this interlude the basic love-motive enters in a new and more powerful form on the brass. It is still in the minor but now it is slow and drawn out, like the lament of love itself, expelled from this world of naked power.

EX. 99: FREIA (2ND SEGMENT, SLOW, MINOR)

This powerful form of the basic love-motive, slow and in the minor, attaches itself to Wotan in Act Two of Walküre where he realises his own lovelessness. He sings it at the beginning of a passage we heard earlier-the one illustrating the use of the second form of the Renunciation Motive as a cadence expressing futility.

EX. 100: FREIA (2ND SEGMENT, SLOW, MINOR)

This lamenting form of the basic love-motive also attaches itself to Siegmund and Sieglinde in a more lyrical way. In Act One of Walküre when Siegmund momentarily feels that his love for Sieglinde is a forlorn hope, the definitive, slow major form of the basic love-motive, which has been associated with their falling in love, now turns sadly to its minor form.

EX. 101: FREIA (2ND SEGMENT, SLOW, MINOR)

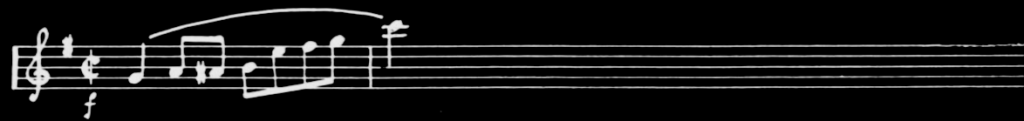

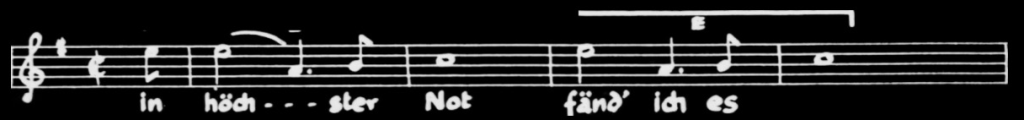

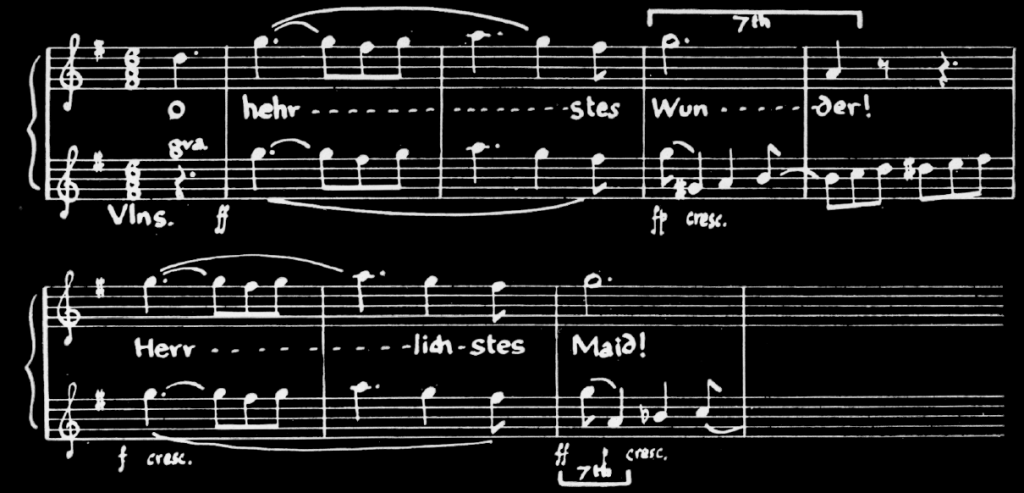

The definitive, slow major form of the basic love-motive later transforms itself freely to generate two new motives associated with the love of Siegfried and Brünnhilde in Act Three of Siegfried. First it forms the basis of the exultant theme known as the motive of ‘Love’s Greeting’; they introduce this vocally when they hail the memory of Sieglinde, as the mother of Siegfried.

The relationship between this new motive of Love’s Greeting and the basic love- motive becomes entirely clear in a later passage, when Brünnhilde tells Siegfried that she was destined for him before he was born. This new motive enters on the woodwind, but Brünnhilde immediately continues it in the shape of the basic love-motive.

EX. 103: LOVE’S GREETING AND FREIA (2ND SEGMENT)

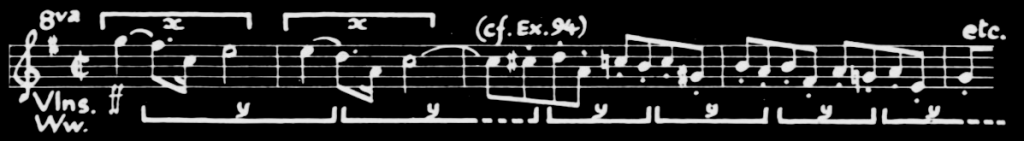

1. The other new motive generated by the basic love-motive is the bold one known as Love’s Resolution: it strikes in nearly at the end of Siegfried to sum up the supremely confident character of the love of Siegfried and Brünnhilde.

This motive is again a free transformation of the basic love-motive; its origin is the brilliant orchestral passage at the end of Act One of Walküre when Siegmund and Sieglinde fall into one anothers’ arms. The basic love-motive enters here in the major, but quickly: then it is developed in a swift, telescoped form to express the joyful passion of the two lovers.

EX. 104: FREIA (SECOND SEGMENT, QUICK, MAJOR)

It is this swift telescoped form of the basic love-motive that broadens out majestically on the horns, at the end of Siegfried, to become the motive of Love’s Resolution.

EX. 105: LOVE’S RESOLUTION

This ends the family of motives generated by the basic love-motive, but there are several other motives associated with the symbol of love which are quite independent. First, there, is the’ moving motive which represents the Bond of Sympathy between the Volsungs – Siegmund and Sieglinde – and later attaches itself to their son Siegfried. It is first heard in Act One of Walküre; it enters in the bass with Sieglinde’s motive above it, when Siegmund and Sieglinde find themselves partners in distress.

EX. 106: THE VOLSUNGS’ BOND OF SYMPATHY

This motive is developed in several different ways throughout the whole drama. When it later attaches itself to Siegfried it takes on a quick, excited form to express his agitation during his love scene with Brünnhilde.

EX. 107: THE VOLSUNGS’ BOND OF SYMPATHY (2ND FORM)

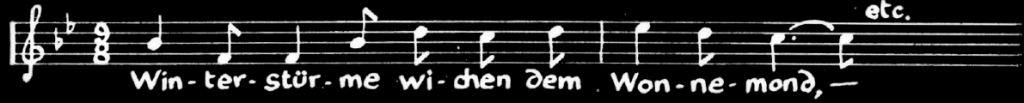

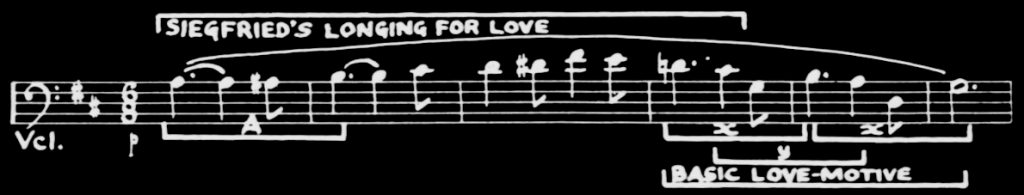

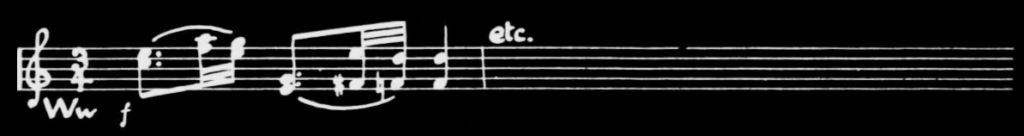

Another independent love-motive associated with Siegmund and Sieglinde is the melody of Siegmund’s song of Spring – ‘Wintersstürme’.

EX. 108: WINTERSSTÜRME

One of the independent love-motives is associated with Wotan’s affection for Brünnhilde: he sings it near the end of Walküre just before he plunges Brünnhilde into her magic sleep.

EX. 109: WOTAN’S AFFECTION FOR BRÜNNHILDE

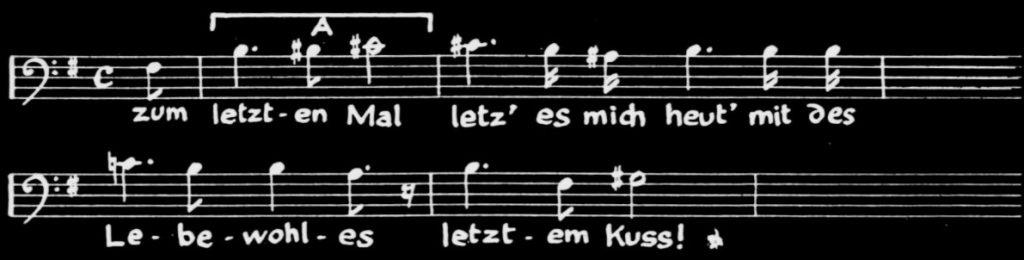

2. There are several independent love-motives attached to Siegfried and the love between him and Brünnhilde. First there is the yearning one associated with Siegfried’s longing for human love and companionship.

He is to replace Wotan in Brunnhilde’s affections: and this motive begins with the same three rising chromatic notes as the one we have just heard, associated with Wotan’s affection for her. It enters in Act One of Siegfried, while Siegfried describes to Mime how he has watched the wooing and mating of the birds in the forest. It is worth noting that this motive goes straight over into the basic love-motive.

EX. 110: SIEGFRIED’S LONGING FOR LOVE

There are four independent love-motives associated with Siegfried and Brünnhilde. The first is a jubilant leaping one, which enters when Brünnhilde is fully awake, and is generally known as the motive of Love’s Ecstasy.

EX. 111: LOVE’S ECSTASY

Two of the other independent love-motives attached to Siegfried and Brünnhilde are simply two of the themes that belong to the Siegfried Idyll. The first, which is not a motive in the strict sense, in that it never recurs, is the opening theme of that work, which is introduced to represent Brünnhilde as the ‘immortal beloved’.

EX. 112: THE IMMORTAL BELOVED

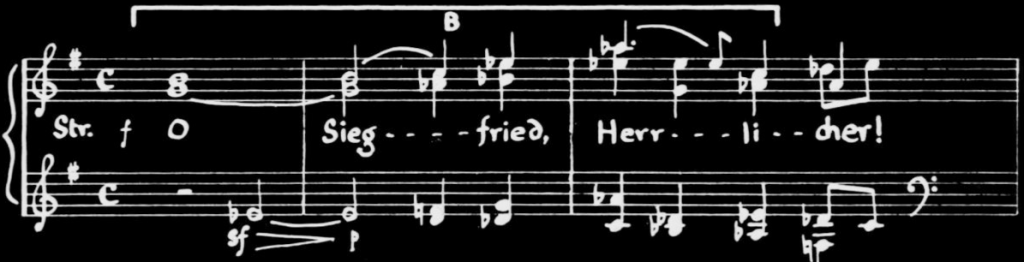

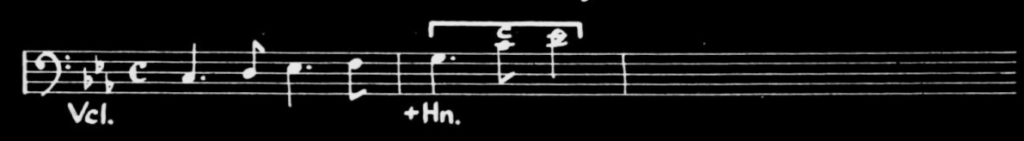

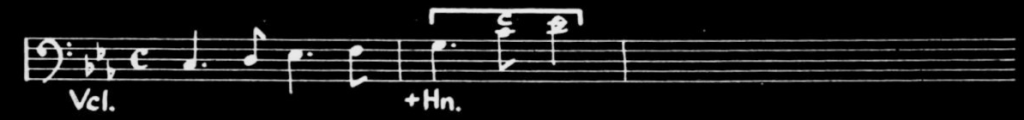

The other motive is the second theme of the Siegfried Idyll, which is sung by Brünnhilde to the words ‘0 Siegfried, treasure of the world’, and has become known in consequence as the motive of the World’s Treasure.

EX. 113: THE WORLD’S TREASURE

This motive does recur; and derive from it is the final independent love-motive – the one associated with Siegfried and Brünnhilde in Götterdämmerung and known as the motive of Heroic Love.

3. The characters in whose lives love plays such an important part – Siegmund and Sieglinde, Siegfried and Brünnhilde – are heroic figures, fighting to establish the claims of love in the loveless world of the ring and the spear. And these figures, taken together, form another of the central symbols of the drama-the symbol of heroic humanity. They are all offspring of Erda by Wotan, in one way or another: Brünnhilde is literally so, and the Volsungs, though born to Wotan by a mortal woman, are begotten by him out of the inspiration of his first encounter with Erda in Scene Four of Rhinegold.

And the basic motive, or basic phrase, which generates the family of motives associated with these heroic characters, is the last three-note segment of the motive of Erda herself. Erda’s Motive is in the minor key, and so are the heroic motives derived from it; but they are all powerful brass motives, and so the minor key here is an expression not so much of pure tragedy as of tragic heroism.

These motives all begin where Erda’s climbing motive leaves off, as it were; they take the last three notes of it as a starting point. We will hear first another special illustration – Erda’s Motive played by the cellos with a solo horn emphasising the last three notes.

EX. 115: ERDA

The leaping motive of the Valkyries, associated particularly with Brünnhilde, springs boldly out of the last three notes of Erda’s Motive.

EX. 116: THE VALKYRIES

The second heroic motive generated by the final segment of Erda’s Motive is the one associated with the Volsung Race, and more particularly with Siegmund. It enters in Act One of Walküre when Siegmund has finished describing his unhappy fate. Here is the special illustration of Erda’s Motive again.

ERDA – EX. 115

And here is the motive of the Volsung Race which rises slowly out of the last segment of Erda’s motive.

EX. 117: THE VOLSUNG RACE (MAIN SEGMENT)

Incidentally, it should be noticed that this motive of the Volsung Race has another segment, expressing a sense of infinite sorrow rather than dark tragedy. It is sung by Siegmund to introduce the main part of the motive which we have just heard.

EX. 118: THE VOLSUNG RACE (FIRST SEGMENT)

The final segment of Erda’s Motive generates another heroic motive associated with the Volsungs. This is the dark one introduced in Act Two of Walküre, when Brünnhilde warns Siegmund of his impending death. It is later attached to Siegfried as doomed hero in Götterdämmerung. Here is the special illustration of Erda’s Motive again:

ERDA—EX. 115

And here is the motive of The Annunciation of Death as it recurs on the orchestra near the end of Götterdämmerung, when Brünnhilde calls for a funeral lamentation worthy of the dead Siegfried. It too rises slowly out of the final segment of Erda’s Motive.

EX. 119: THE ANNUNCIATION OF DEATH

The culminating heroic motive generated by the last segment of Erda’s Motive is the indomitable one of Siegfried. Here is the special illustration of Erda’s Motive once more.

ERDA—EX. 115

And here is Siegfried’s Motive. Like the Valkyrie Motive it springs boldly out of the last segment of Erda’s Motive.

EX. 120: SIEGFRIED

4. One further motive belongs to this heroic family - perhaps surprisingly; this is the motive of Gunther in Götterdämmerung. Gunther does not belong to the offspring of Wotan and Erda in any sense.

Yet he too is a hero, who in his own way tries to establish the claims of love – an attempt which takes a warped form only because of his weakness, which makes him a pawn in the evil plot of his half- brother Hagen. His motive belongs unmistakably, if less than magnificently, to the same heroic family as those associated with the Valkyries and the Volsungs.

EX. 121: GUNTHER

So much for the heroic characters of the drama. The two central male ones are Siegmund and Siegfried, and the dynamic symbol of their heroism is the Sword created by Wotan, which each of them makes his own. And just as the motives associated with the heroes themselves stem from the motive of Erda – which is a form of the Nature Motive – so the motive representing the Sword springs from the Nature Motive itself. Indeed we heard earlier that it is a member of the Nature family, being almost identical with the original arpeggio form of the Nature Motive.

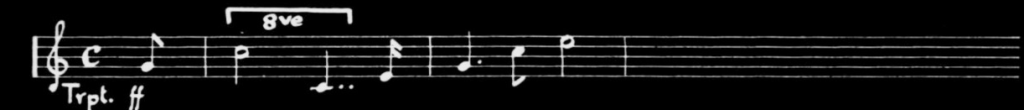

5. The Sword Motive recurs many times in the drama, but now we must consider it as another of the basic motives, which generates a whole family of motives associated with heroism in action. It first enters on the trumpet in Scene Four of Rhinegold, when Wotan conceives the idea of the Sword, and of the hero who shall wield it; and we may notice that the musical interval on which it revolves is a downward-leaping octave.

EX.122: THE SWORD

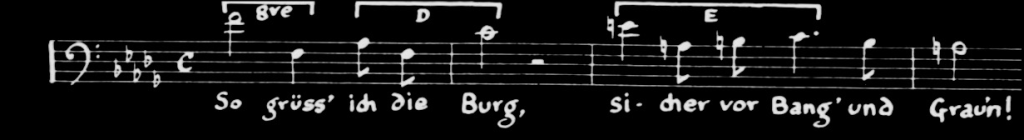

This is merely the first segment of the Sword Motive. There is a much fiercer second one following immediately: and this too is based on the interval of a downward-leaping octave. It is sung by Wotan as he explains the purpose of the sword – to secure Valhalla against any attack by enemies: and like the first segment it recurs later in the drama.

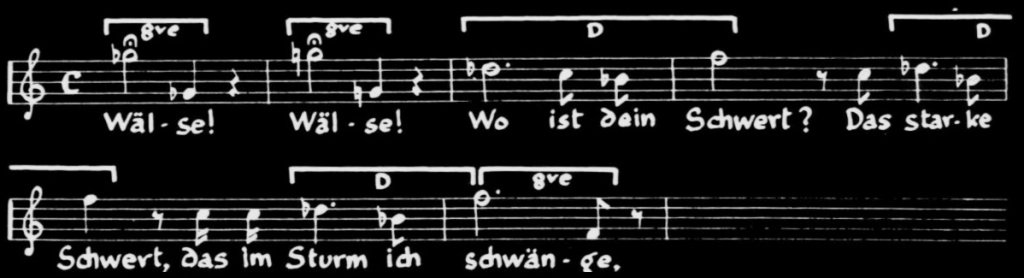

Siegmund sings it in Act One of Walküre when he remembers that his father – Wälse – who is of course Wotan – had promised him a sword in his hour of need. Here first is the second segment of the Sword Motive, with its downward-leaping octave, as sung by Wotan in Scene Four of Rhinegold to indicate the Purpose of the Sword.

EX. 123: THE PURPOSE OF THE SWORD

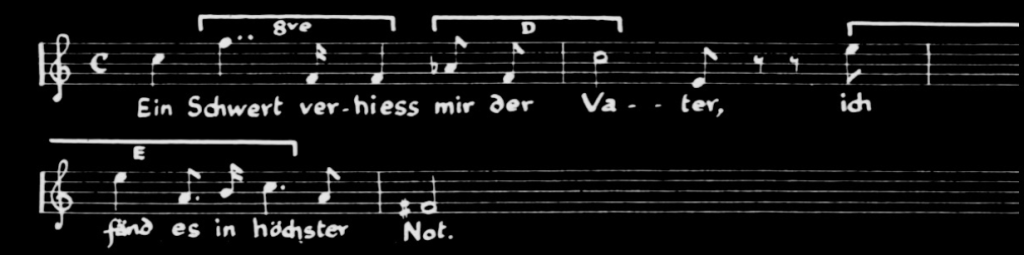

And here is the same segment of the Sword Motive as sung more quickly by Siegmund in Act One of Walküre

EX. 124: THE PURPOSE OF THE SWORD (SIEGMUND)

When Siegmund goes on to apostrophise his father, asking him where the sword is, his voice isolates the downward-leaping octave, common to both segments of the Sword Motive, and it becomes a motive in its own right.

EX. 125: ‘WÄLSE!’

Near the end of Act One of the Walküre, when Siegmund draws the sword from the tree and names it Nothung – or Need – the new motive of the simple downward- leaping octave attaches itself to the name.

EX. 126: ‘NOTHUNG !’

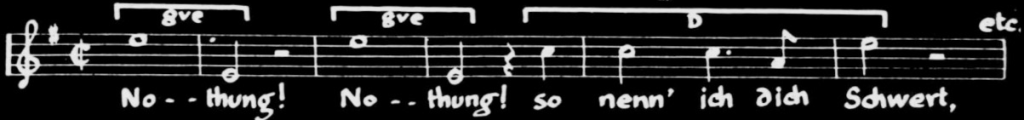

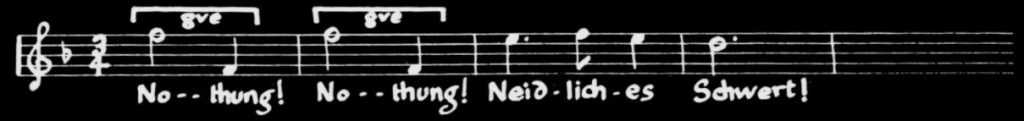

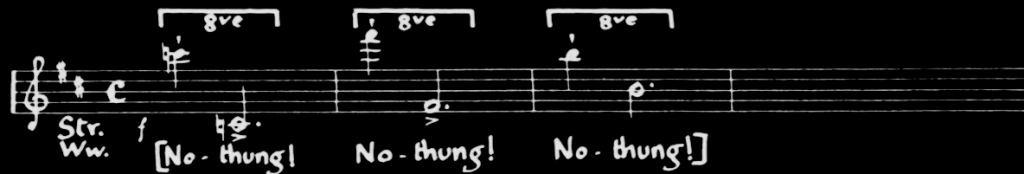

This Nothung Motive, associated with the her’s need for the sword, recurs in another form in Act One of Siegfried. Siegfried sings it when he re-forges the sword and re-names it Nothung.

EX. 127: ‘NOTHUNG !’ (SIEGFRIED)

This downward-leaping octave, stemming from the Sword Motive, is used to generate, another heroic motive in Act One of Götterdämmerung. This is the terse motive of Honour which enters on the orchestra when Siegfried draws the sword to lay it between himself and Brünnhilde, to keep faith with Gunther.

EX. 128: HONOUR

Another important phrase of the Sword Motive is the latter half of its second segment, referring to the preservation of Valhalla through the sword. The important interval here is a downward leap of a fifth followed by two steps upward. Let Wotan remind us of this phrase.

EX. 129: THE PURPOSE OF THE SWORD (SECOND HALF)

This phrase is also taken Up by Siegmund in Act One of Walküre. He sings it twice over as he grasps the sword to draw it from the tree, still remembering his father’s promise.

EX. 130: THE PURPOSE OF THE SWORD (SECOND HALF. SIEGMUND)

6. Ironically, this phrase, with its downward leap of a 5th followed by two steps upwards, generates a number of motives associated with the various characters and events which stand in the way of Wotan’s plans to ensure the safety of Valhalla. In the first place it forms the basis of the orchestral motive attached to Fricka in Act Two of Walküre, when she argues Wotan into abandoning Siegmund and the sword, and also the purpose for which both were conceived.

EX. 131: FRICKA IN ’VALKYRIE’

In Act One of Götterdämmerung the same phrase, with its downward leap of a 5th, generates further new motives associated with the Gibichungs — who stand in the way of the new possessor of the sword, Siegfried. The first is the motive of Friendship – the illusory friendship between Siegfried and Gunther.

EX. 132: FRIENDSHIP

Behind the illusory friendship between Siegfried and Gunther stands Hagen: and his own personal motive isolates the downward leap of a 5th in its sinister diminished form. It usually enters in the bass, as here, in Hagen’s Watch-Song.

EX. 133: HAGEN

Hagen’s plan is to use the friendship between Siegfried and Gunther to seduce Siegfried away from Brünnhilde into a marriage with Gutrune: and the motive associated with this seduction is a freer transformation of the original phrase, with the downward leap altered from a 5th to a 7th, but with the two steps upward restored. Hagen introduces It vocally when he refers to the magic potion which is to be the agent of seduction.

EX. 134: SEDUCTION

The half-unwitting instrument of the seduction, Gutrune, has her own personal motive; and this practically returns to the original form of the phrase with its downward leap of a 5th, followed by two steps upward, but now with much sweeter harmonies.

EX. 135: GUTRUNE

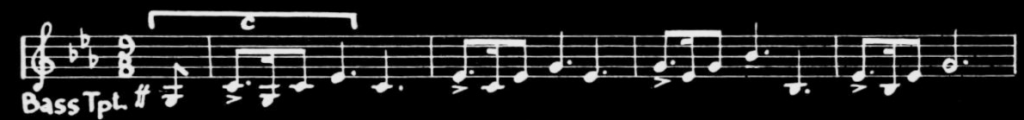

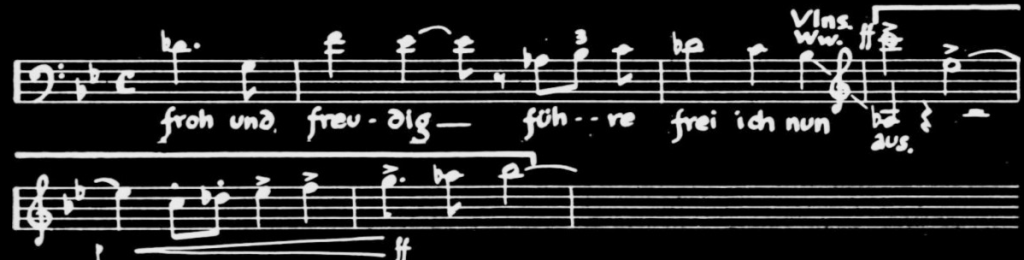

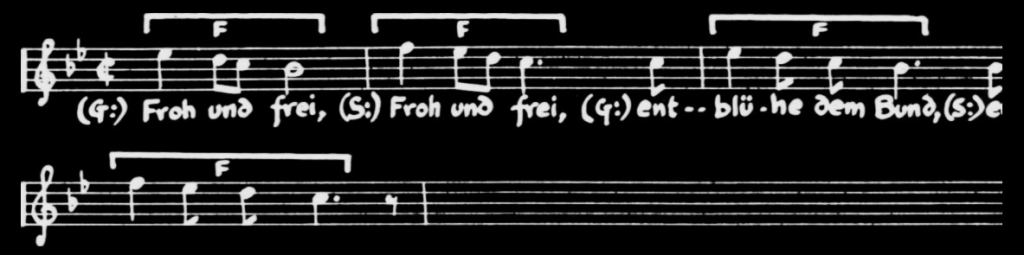

7. Closely associated with Gutrune’s Motive is the horn-call of the Gibichungs, which punctuates Hagen’s rallying-call to the Vassals in ActTwo of Götterdämmerung.

EX. 136: THE GIBICHUNG HORN-CALL

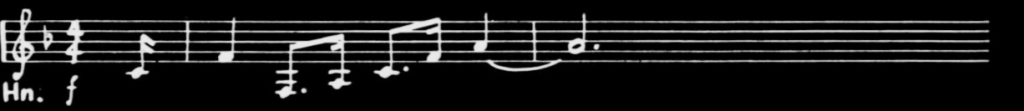

A further motive belonging to this family is that of Siegfried’s Horn. This is a direct antithesis of the Gibichung horn-call which we have just heard-it begins with an upward leap of a 5th instead of a downward one.

EX. 137: SIEGFRIED’S HORN-CALL

In the Prelude to Götterdämmerung this original fast version of the horn motive takes on a more majestic form, representing Siegfried’s new stature as the active hero inspired by the love of Brünnhilde.

EX. 138: SIEGFRIED’S HORN-CALL (SECOND VERSION)

During the great scene in Act Two of Götterdämmerung, in which Siegfried and Brünnhilde both swear on Hagen’s spear, there is a tremendous conflict between the upward and downward-leaping 5ths. The result is the motive known as The Swearing of the Oath.

EX. 139: THE SWEARING OF THE OATH

One other motive belonging to this family should be mentioned – that of the World’s Inheritance, which enters in Act Three of Siegfried. This motive, in which the salient interval is a downward-leaping 6th, followed by several steps upwards, bursts in on the orchestra to round off Wotan’s statement to Erda that he intends to let Siegfried and Brünnhilde inherit the world.

EX. 140: THE WORLD’S INHERITANCE

8. Here we come to the end of the family of heroic motives generated by the motive of The Sword, with its downward leaping octave and 5th. But the symbol of heroism, like the symbol of love, has other independent motives attached to it.

One of the most important of these is that of Siegfried’s Mission, which consists of a descending phrase of four notes, repeated in falling sequence. It follows him on the orchestra as he dashes away into the forest in Act One of Siegfried, on discovering to his delight that he can be free of Mime, who has no claim on him at all.

EX. 141: SIEGFRIED’S MISSION (1ST VERSION)

This motive of Siegfried’s Mission achieves its definitive broad form in the Prelude to Götterdämmerung. He sings it himself in his duet with Brünnhilde, when he declares that he is no longer Siegfried but Brünnhilde’s arm.

EX. 142: SIEGFRIED’S MISSION (DEFINITIVE)

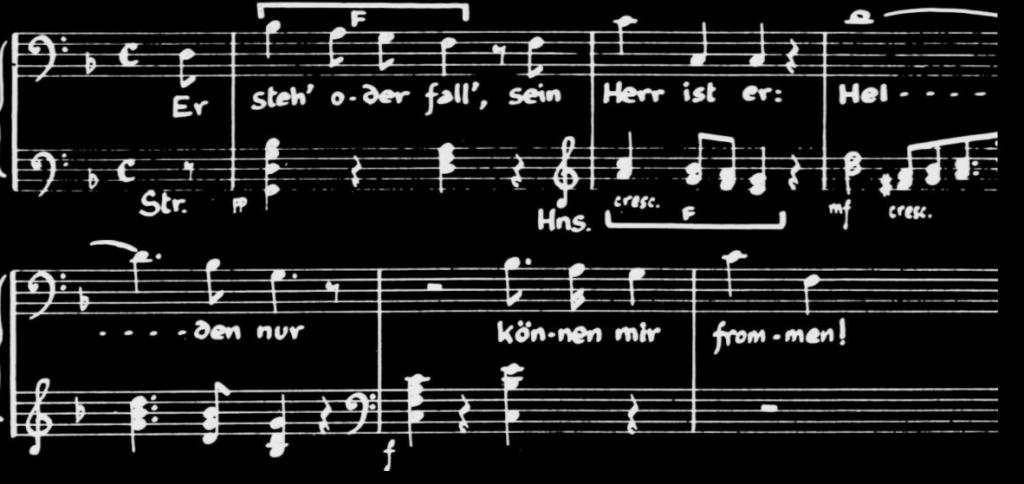

Another form of this motive, with the falling phrases in rising sequence, is introduced by Wotan in Act Two of Siegfried. He sings it when he assures Alberich that Siegfried is an entirely free agent, who must stand or fall by his own powers.

EX. 143: SIEGFRIED’S MISSION (WOTAN VERSION)

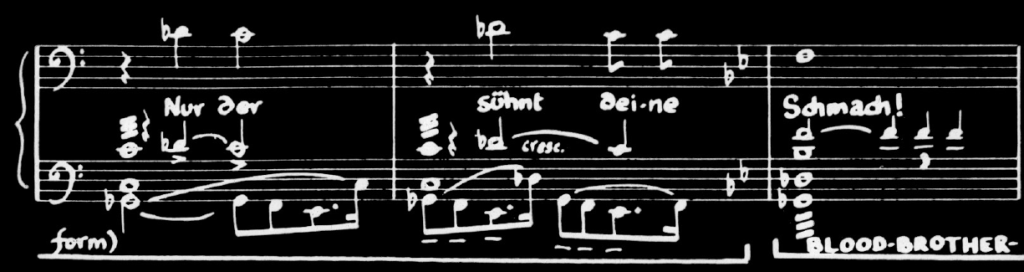

In this form the motive of Siegfried’s Mission forms the basis of the blood- brotherhood duet in Act One of Götterdämmerung. It enters when they sing of their freedom swearing the oath; and the effect is one of dramatic irony, since they are both acting mere pawns in Hagen’s plot.

EX. 144: SIEGFRIED’S MISSION (IRONIC)

The relationship of this passage to the motive of Siegfried’s Mission makes clear that the descending main theme of the blood-brotherhood duet is itself generated by the motive.

EX. 145: BLOOD-BROTHERHOOD

This main theme of the blood-brotherhood duet itself occurs with great dramatic irony in Act Two of Götterdämmerung. It enters powerfully on the horns when Gunther, finding himself inextricably involved in Hagen’s plot to kill Siegfried, remembers oath of blood-brotherhood he swore with him.

This completes the large number of motives associated with the symbol of heroism in connection with Wotan, Siegmund and Siegfried.

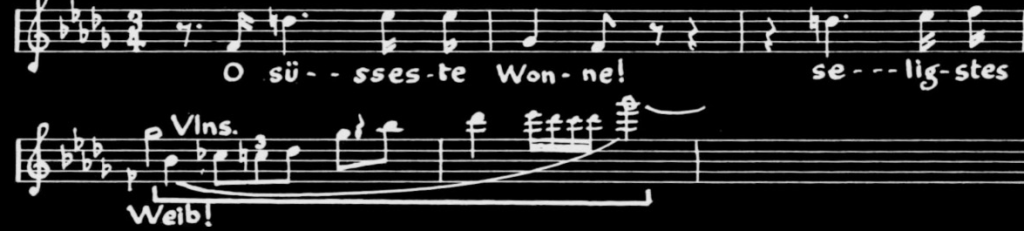

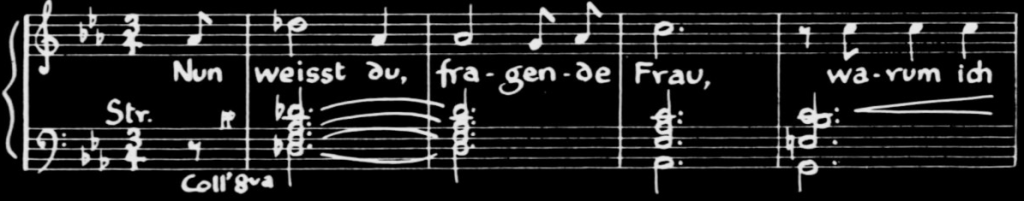

9. Complementary to this symbol is that of the inspiration given to heroes by women, which is represented by the main female characters of the drama – Fricka, Sieglinde and Brünnhilde, each of whom has a motive of this kind. As with the symbol of love, the symbol of women’s inspiring power begins on a subdued level in the power-ridden world of Rhinegold.

The basic motive is the one introduced by Fricka in Scene Two: she sings it when she holds out to Wotan the lure of a comfortable life of Domestic Bliss in Valhalla as a satisfying ideal in itself, without any need of further striving. The basis of the motive is two falling intervals — a 7th and a 5th.

EX. 147: DOMESTIC BLISS

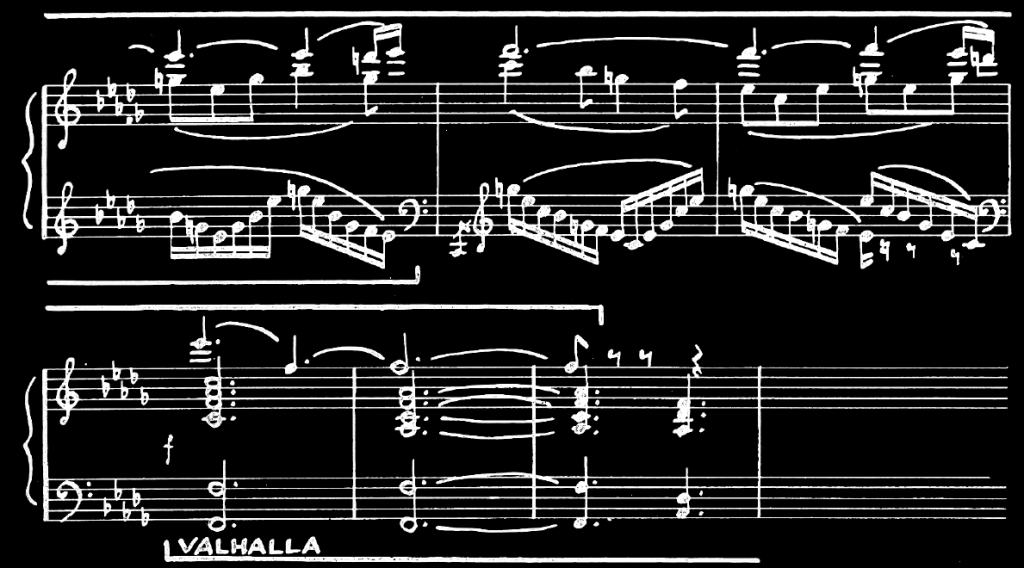

Little more is heard of this motive; but in Act Three of Walküre, where the struggle between love and power reaches its height, it is suddenly transformed and lifted on the heroic plane. Sieglinde, when she learns that she is to bear Siegfried, the hero of the future, sings the ecstatic motive of Redemption. This is also characterised by two falling intervals, both being falling 7ths.

EX. 148: REDEMPTION

The third motive associated with the inspiring power of woman is Brunnhilde’s personal motive in Götterdämmerung, when she has been transformed from a Valkyrie into a mortal woman and Siegfried’s wife. Again we notice the falling 7ths.

EX. 149: BRÜNNHILDE AS MORTAL WOMAN

This ends the family of motives associated with the inspiring power of woman; although few they are extremely powerful.

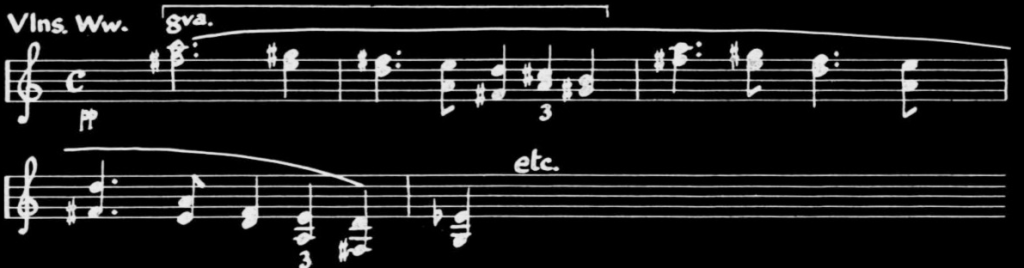

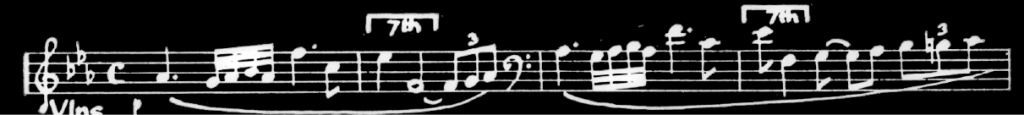

10. One last central symbol remains to be considered — the sense of the mysterious and inscrutable that surrounds human life. The central character here is Loge, the central symbol his Magic Fire; and his flickering chromatic motive is the basic one which generates the rest of this family. It enters on the orchestra in Scene Two of Rhinegold when he himself makes his long-awaited entry, much to Wotan’s relief.

Loge’s Motive consists of several segments: the most important one is that associated with the Magic Fire, which we can hear clearly from a special illustration – the segment played by the orchestra alone.

EX. 151: MAGIC FIRE

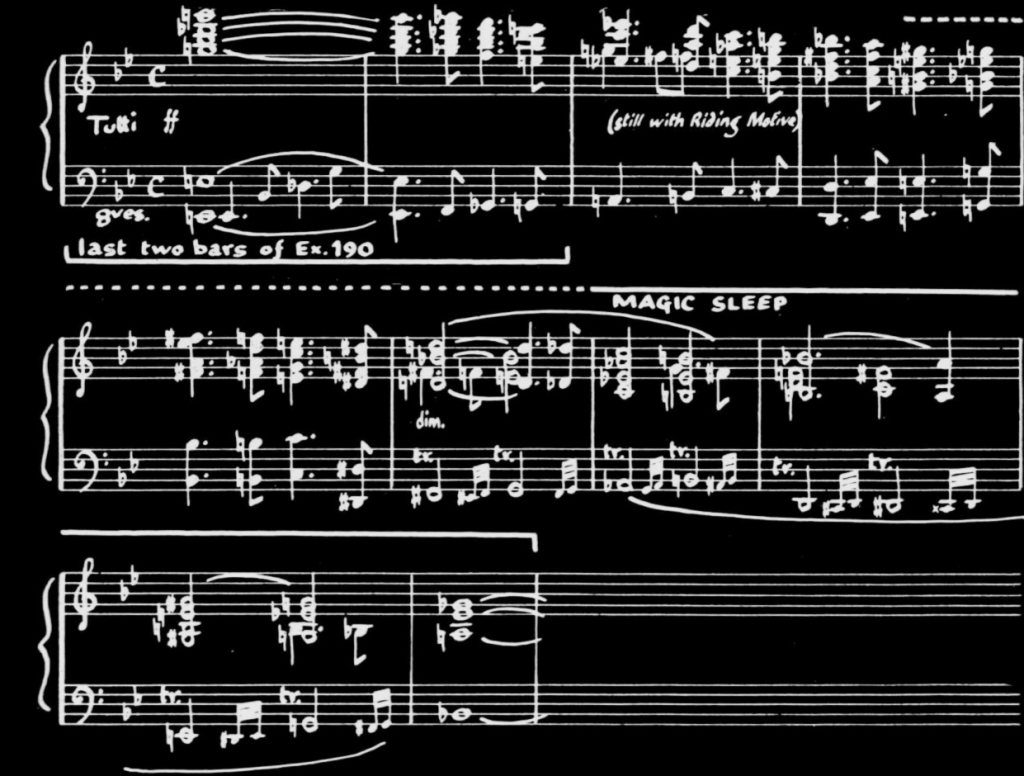

This is the segment of Loge’s Motive which dominates the final scene of Walküre, where Wotan calls on Loge to surround the sleeping Brünnhilde with a wall of magic fire.

EX. 152: MAGIC FIRE (END OF VALKYRIE)

In the meantime this segment of Loge’s Motive has already generated a new motive of magic – that of the Tamhelm, introduced by muted horns in Scene Three of Rhinegold. This is based on the harmonic progression of the Magic Fire segment of Loge’s Motive, slowed down, in the minor, and without its flickering figuration.

EX. 153: THE TARNHELM

The Tarnhelm Motive itself becomes the starting-point of another new motive of magic in Götterdämmerung. In Act One, when Hagen explains the powers of the magic potion to Gutrune, we hear the Tarnhelm Motive in the background with two statements of the sensuous segment of Freia’s Motive in the foreground; and after the second statement of Freia’s Motive the Tarnhelm Motive straightway transforms itself into the elusive new motive of The Potion.

The other important segment of Loge’s Motive is a series of first-inversion chords running up or down the chromatic scale. The version that generates other motives is the descending one.

EX. 155: LOGE (CHROMATIC SCALE SEGMENT)

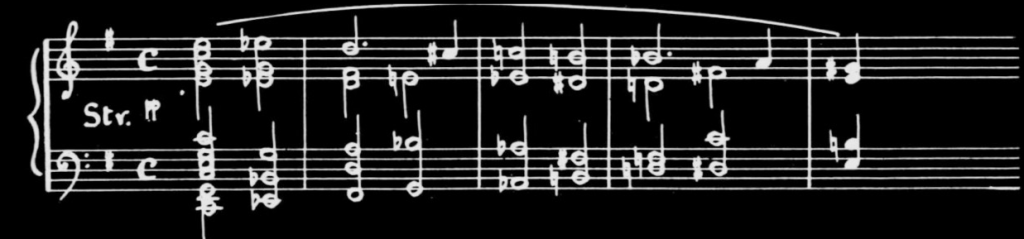

This segment also slows down and loses its flickering figurations, to produce the motive of the Magic Sleep which descends on Brünnhilde in the final scene of Walküre.

EX. 156 THE MAGIC SLEEP

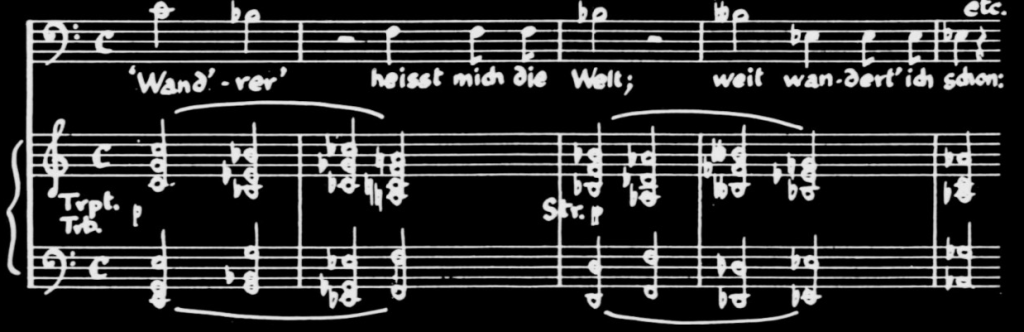

This same segment of Loge’s Motive is more freely transformed to generate the mysterious motive associated with Wotan in his role as the Wanderer in Siegfried. It first appears on the orchestra when he enters Mime’s hut in Act One.

EX. 157: THE WANDERER

11. One further motive connected with magic and mystery is not directly derived from Loge’s Motive, but is related to its general chromatic character. It is one of the shortest, yet one of the most important in The Ring – a chromatic progression of two chords only, which is associated with the inscrutable workings of fate. It first enters on the tubas when Brünnhilde comes to Siegmund in Act Two of Walküre to warn him that he is to die.

EX. 158: FATE

This motive of two chords suggests the workings of fate by moving mysteriously from one key to another with each repetition. But at the very end of Walküre fate is suspended, as it were, while Brünnhilde sleeps; and so the Fate Motive, in spite of its repetitions, is held fixed in the key in which the opera ends.

EX. 159: FATE (END OF VALKYRIE)

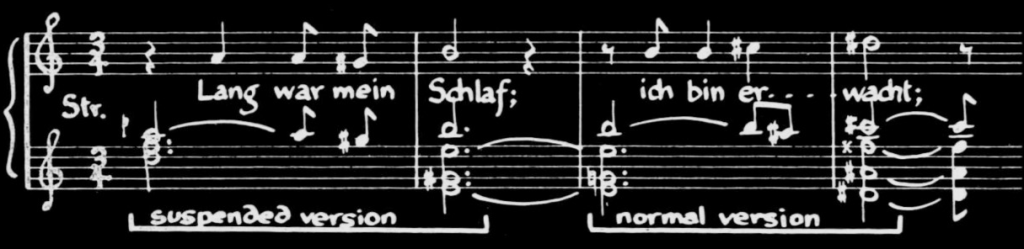

When Brünnhilde is awoken in Act Three of Siegfried, almost her first words are ‘Long was my sleep’ – and she sings this suspended version of the Fate Motive which we have just heard. Then, as she sings ‘I am awake’, the Fate Motive returns to its original form, moving into a new key to suggest that from this point onwards fate is at work again.

EX. 160; FATE (BRÜNNHILDE)

This passage makes clear that the bright motive of two chords to which Brünnhilde actually awakes is itself generated by the Fate Motive, suggesting the working of fate towards a more happy end, at least for the time being.

EX. 161: BRÜNNHILDE AWAKES

This brings to an end the family of motives associated with the symbol of magic and mystery.

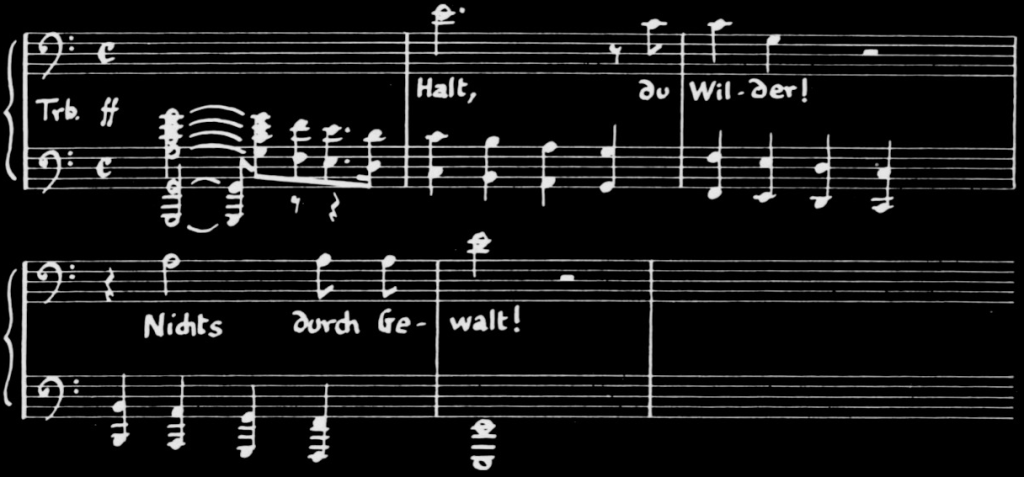

12. There are one or two motives which lie outside the main families, representing simple characters rather than symbols. One of these is the motive attached to Hunding which we heard right at the start; another is the brass motive associated with the Giants in Rhinegold. which is appropriately heavy and forceful.

This motive of the Giants takes on a more sinister form on the timpani in Act Two of Siegfried to represent Fafner, the giant who has survived and turned himself into a Dragon.

EX. 163: FAFNER AS GIANT TURNED DRAGON

It might be wondered, perhaps, why some characters seem to have no personal motive at all. There is a Siegfried motive, for example, and a Brünnhilde motive, but the commentators list no Alberich motive. Alberich is of course sufficiently represented by the symbolic motives attached to him – those of the Ring, the Power of the Ring, Resentment, Murder, and so on. But in fact he does have a personal motive of his own.

When Alberich enters in Scene One of Rhinegold we hear some uneasy music in the depths of the orchestra, portraying his awkward attempts to clamber up out of Nibelheim into the waters of the Rhine.

EX. 164: ALBRICH

Those furious little descending figures on the cellos are in fact Alberich’s personal motive; we can hear them more clearly from an illustration played by the cellos alone, a little more slowly.

EX. 165: ALBERICH (CELLOS)

This personal motive of Alberich’s forms part of the general transformation of the music of Scene One of Rhinegold into that of Scene Three which we noticed earlier. When Alberich enters in the Nibelheim scene, this furious descending motive of his accompanies the blows he inflicts on Mime. Once more the music reveals that the thwarting of his desire for the Rhinemaidens has been transformed into a sadistic lust to get his own back on everybody.

Mime too has his personal motive-even several of them. The most important is a whining one, a kind of insidious transformation of the furious descending one of Alberich. He introduces this vocally when he sings what Siegfried calls his ‘starling- song’, about how he brought the boy up as a baby.

EX. 167: MIME’S ‘STARLING-SONG’

Incidentally, this whining motive of Mime and the furious motive of Alberich, of which it is a transformation, are both distorted minor versions of the bold descending major motive of Siegfried’s Mission, which is of course directly opposed to the machinations of the two dwarfs.

EX. 168: SIEGFRIED’S MISSION

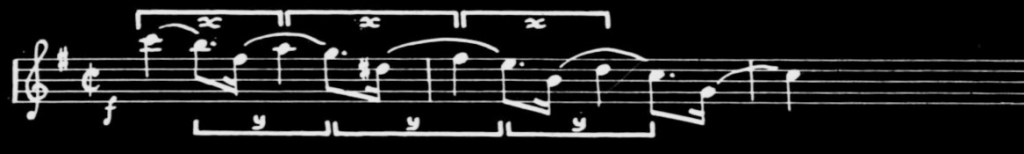

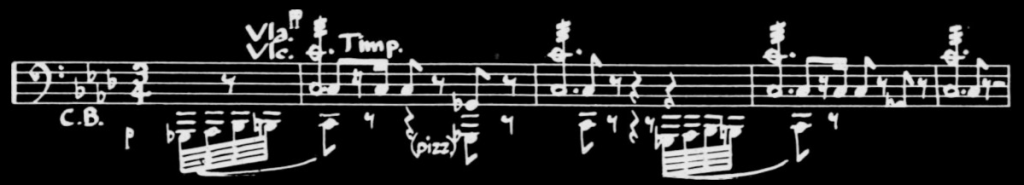

13. These motives of Alberich and Mime are only two of the many subsidiary motives in The Ring. These are too numerous for every single one to be enumerated, but some of them claim our attention. Sometimes, and especially In Götterdämmerung, subsidiary motives are introduced and then developed in such a subtle way that they have no simple primary meaning, but gather meaning as they proceed.

One example of many is the motive representing the Dawn in Act Two of Götterdämmerung, when Hagen wakes up after his nocturnal communion with his father Alberich. As first introduced by the bass clarinet, this motive’s arpeggio- shape proclaims it an offshoot of the nature family.

EX. 169: DAWN

Soon however this Dawn Motive is developed forcibly by the horns and its main figure eventually assumes a rather brutal character, much more in keeping with the personality of Hagen than with the simple natural phenomenon of dawn. The day that is dawning is going to be Hagen’s day.

EX. 170: DAWN (HAGEN’S DAY)

Later this motive forms the choral song of the Vassals as they sing Hagen’s praises and declare themselves ready to stand by him. By now it clearly is Hagen’s day.

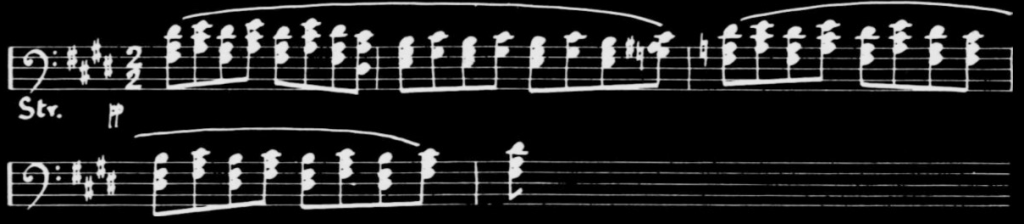

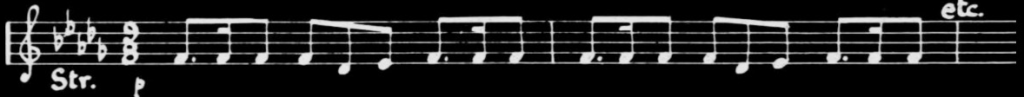

EX. 171: THE VASSALS’ SONG

14. Quite a number of the subsidiary motives are not so much recurrent themes representing symbols as recurrent figurations portraying movement and activity. There is one group in particular which is a kind of family representing various aspects of nature in motion. The starting-point is a swift rising and falling major-key figuration on the violins in Scene One of Rhinegold: it is repeated over and over to portray the waters of the Rhine rippling around the swimming Rhinemaidens.

EX. 172: WAVE-MOTION (RHINE VERSION)

We can identify the shape of this motive more clearly if we have it played by the violins alone, and a little more slowly. It is a swift surge upwards followed by a longer and not quite so swift descent – like the flow and ebb of a wave.

EX. 173: WAVE-MOTION (RHINE VERSION)

In Scene Two of Rhinegold, when Loge refers to the universal burgeoning of nature, the orchestra transforms this flowing and ebbing Wave-Motion shape into a much slower undulation, more appropriate to the earth.

EX. 174: WAVE-MOTION (DEFINITIVE)

This is the definitive form of the motive of Nature in Motion, the form in which it will usually recur. We hear it when Siegfried is in the forest, feeling nature all around him, and when Wotan addresses Erda as the wise woman who knows all the secrets of nature. And it transforms itself to generate other motives portraying different aspects of nature in motion.

A notable case is its swift minor-key transformation as the motive of the Storm which opens Walküre. The actual notes of the motive, as we heard earlier, are derived from the Spear Motive, but the melodic and rhythmic pattern in which they are deployed is that of the wave-motion motive, surging swiftly upwards on the cellos and basses and less swiftly down again.

EX. 175: THE STORM

The final transformation of the motive of Nature in Motion occurs in the last Act of Götterdämmerung. Here it changes back into something like its original watery form on the violins, to portray the Rhine rippling around the Rhinemaidens again.

EX. 176: WAVE-MOTION (GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG)

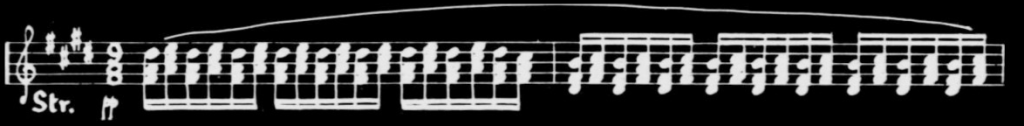

15. Besides this family of motives representing Nature in Motion there are a considerable “number portraying various physical activities; but it will be obvious by now that to account for every last subsidiary motive in The Ring, and to indicate its position in the general scheme of things, would be an almost endless task. And so we may end by examining one or two instances of the way in which Wagner builds up his motives into larger wholes. And we may consider first three examples of what might be called ‘Composite Motives’.

The first is a combination of elements from two motives which could hardly be in greater contrast with each other – those of Valhalla and Loge. It occurs in Scene Three of Rhinegold when Loge is pretending to be impressed by Alberich’s ambitions to rule the world instead of Wotan. Let us remind ourselves first of the main segment of the Valhalla Motive and notice how it proceeds by repeating a short phrase over and over.

EX. 177: VALHALLA

And now let us hear one of the many segments of Loge’s Motive — one that first enters when he is making fun of Alberich in Scene Three of Rhinegold.

EX. 178: LOGE TAUNTING ALBERICH

By combining at top speed the repeated figure of the Valhalla Motive with this segment of Loge’s Motive, Wagner evolves the flippant composite motive which accompanies Loge’s mockery of Alberich’s ambitions.

EX. 179: VALHALLA-LOGE (COMPOSITE MOTIVE)

Our second example of a Composite Motive is connected with Siegfried: it combines the motives of the Sword and Siegfried’s Horn, at top speed, to represent Siegfried’s indomitable vitality. Here first is the Sword Motive again.

SIEGFRIED’S HORN-CALL — EX. 137

And now here is the Composite Motive combining the two, as Siegfried plays it on his horn and awakens the sleeping Fafner.

EX. 180: SWORD PLUS HORN (COMPOSITE MOTIVE)

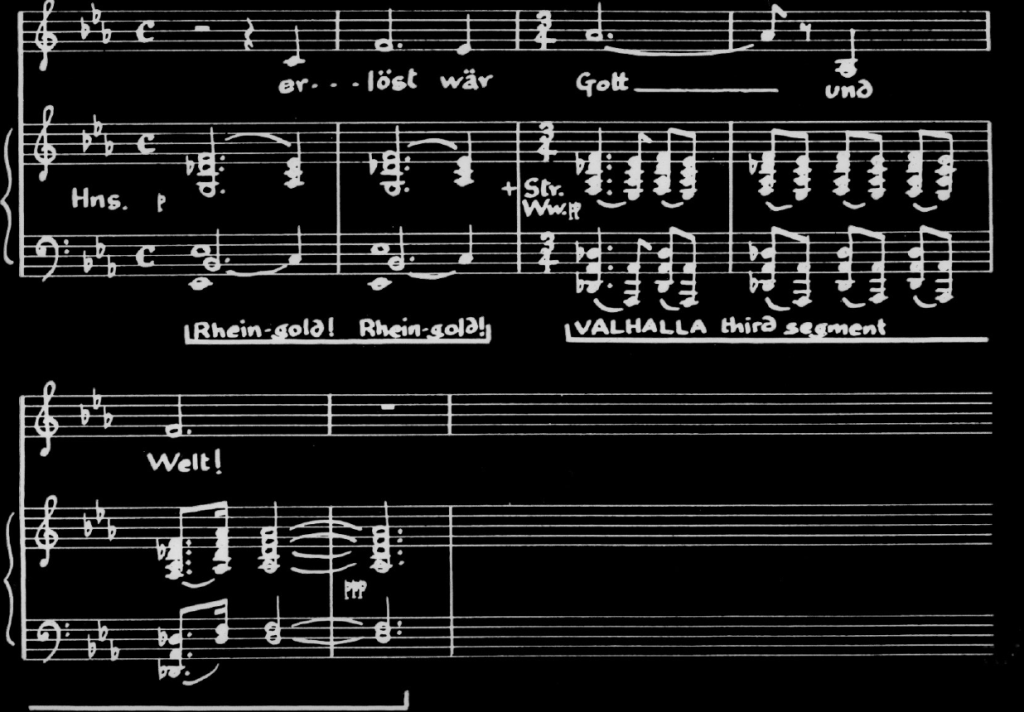

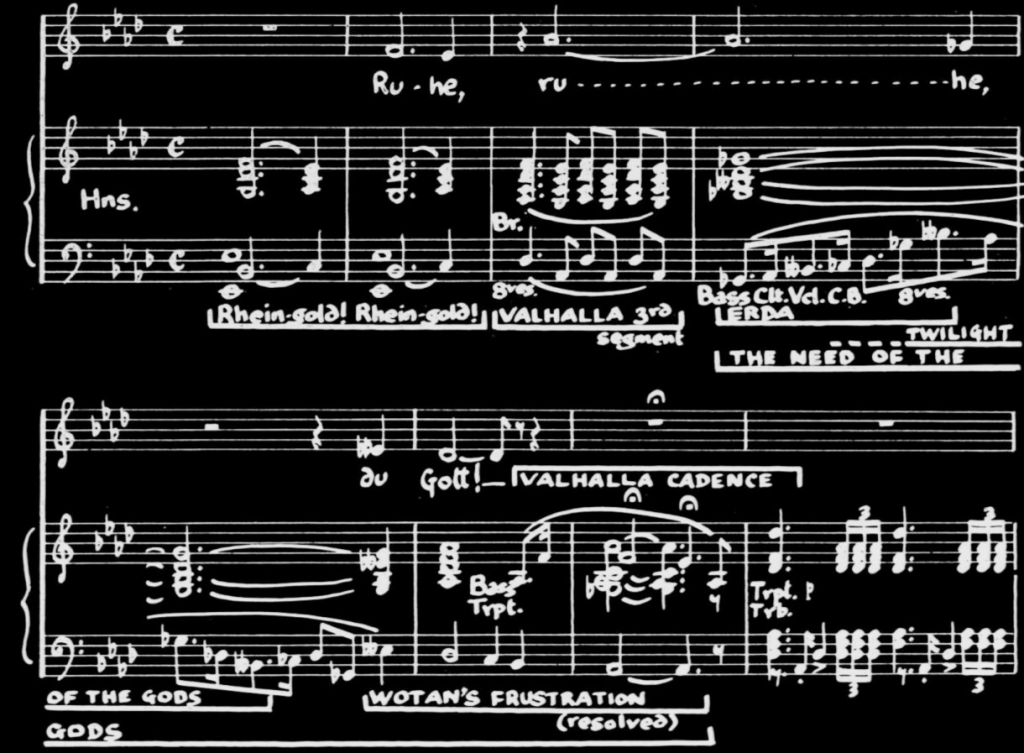

16. Our final example of a composite motive is a longer and more subtle one, connected with Wotan, which first appears in Act Two of Walküre. It is generally known as ‘The Need of the Gods’ and it represents Wotan’s search for a way out of his frustration.

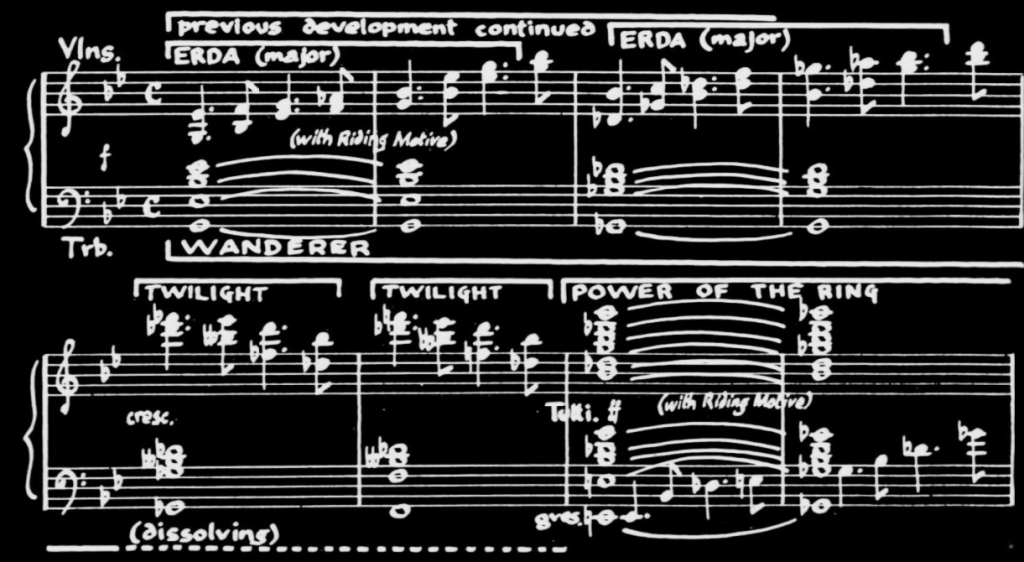

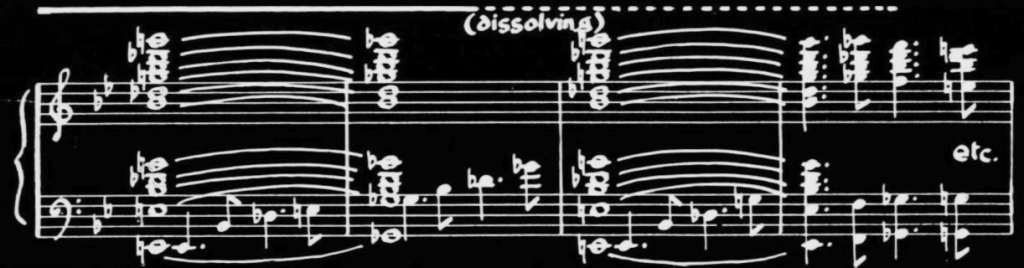

Tormented both by Erda’s warning about the end of the Gods and by the thwarting of his will by his wife Fricka, he wonders how he can find a free hero who will achieve what he is prevented from achieving by his responsibility to the law. As he reflects on this problem we hear the composite motive of The Need of the Gods, which is a speeded-up combination of the single motives of Erda.

The Twilight of the Gods, and Wotan’s Frustration. Here first is the motive of Erda followed by the motive of The Twilight of the Gods, a juxtaposition which occurs, as we have heard, during Wotan’s first encounter with Erda in Scene Four of Rhinegold.

And now here is the combination of those two ideas, speeded up-the composite motive of The Need of the Gods as it enters in the bass, and is developed at length.

EX. 181: THE NEED OF THE GODS (COMPOSITE MOTIVE)